Listowel Writer’s Week, a book of “Navvy” poems, and a Kavanagh work.

By the time you read this, I hope to be in the Culture capital of Ireland at Listowel Writer’s Week.

It will also be the weekend of the Listowel Races when the

less literary members of society will throng to the Island Racecourse.

Thanks to Mary Coby I have the following story from the Listowel Harvest

Festival of Racing in days of yore.

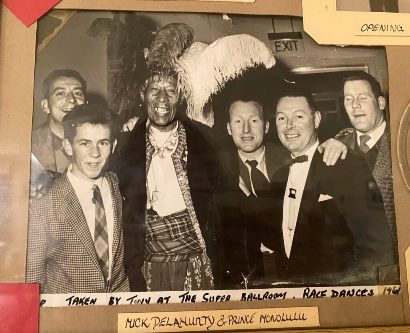

Alice Walsh shares photographic evidence of “the Prince”.

It was taken at Race-week 1961 at the opening of Walsh’s Super Ballroom.

In the centre of the image surrounded by Mick Delahunty band

members is a beloved visitor to Listowel Races, an eccentric tipster

known as Prince Monolulu. He wasn’t a prince and his name wasn’t

Monolulu and he wasn’t an African chief as he claimed.

|

|

In Listowel, in the 1950s and 60s, a black man was a rare enough

sight. A very tall black man dressed like an Ethiopian chief with a

monstrous ostrich plume on his head and a lion’s tooth around his neck

was bound to attract attention. He was a regular on racetracks in

Britain. When not at the races he was a “Lion tamer, fire eater, street

dentist, preacher, tribal chief, boxer, prisoner of war, and

entertainer.”

“He was married six times.” When Spion Kop won the 1920

Derby at odds of 100-6 Monolulu won a reputed £8,000 (worth around

£400,000 in today’s money).

This was all part of the myth that surrounded this man. But

like most “facts’ about this character we have to take everything with a

pinch of salt. Monolulu was American. He came to England and soon

discovered that a life as a showman could be quite a good living in the

early 20th century.

He plied his trade on racecourses until his death in 1965 on

Valentine’s Day. The story goes that he choked on a strawberry cream

from a box of Black Magic. Like everything else about him, this too

sounds a tad implausible.

On his trips to Listowel he would visit The Island armed with a handful of sealed envelopes. “I got a horse to beat the favourite,” was

his cry. He sold you the tip sealed in an envelope and urged you not to

share it so as not to upset the odds. He must have been successful as

he came back year after year. He was part of the colour that was part of

the annual races meeting.

|

|

* * * * *

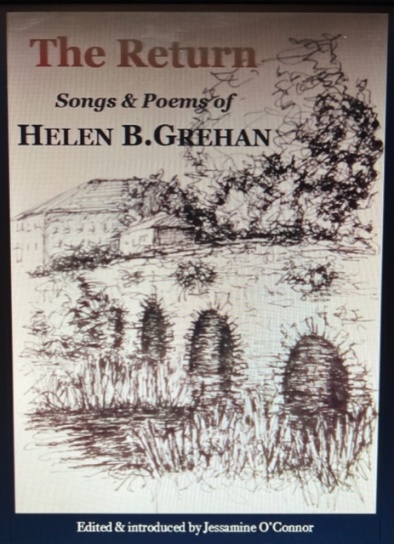

Folk music legend Helen B. Grehan's first book of poems and

songs, 'The Return', was published on May 30th. This collection of the

songs and poems of this Roscommon is edited by Jessamine O’Connor.

Helen B Grehan was born and reared in Boyle County

Roscommon where her parents owned a pub. It was a pub which was famous

as a place where musicians and singers would gather. From a very young

age, Helen began writing down songs of John Reilly, which are preserved

to this day in oral Traveller tradition. Shortly before his death,

Reilly recorded many of his songs at Grehan’s for a visiting UCLA

professor. A plaque to John Reilly is on the wall where Grehan’s bar

stood.

Her career as a public performer stretches back to her

early teens. With her two older sisters, Francis and Marie, she went on

to perform – under the name Bernie – in concert halls

and on festival stages all over Ireland, England, Scotland, and Wales,

including Dublin’s Olympia theatre and London’s Royal Albert Hall. The

Grehan Sisters played a range of venues including The Rose of Tralee,

The Edinburgh Festival, The Wild Geese Club, and major folk festivals

where they shared space with Ronnie Drew and the Dubliners, The

Incredible String Band, The Furey Brothers, Christy Moore, The Clancy

Brothers, Ralph McTell, and Billy Connolly – who called them “fearsome”.

She also plays with the Boyle Songwriters Circle and recorded ‘Where

Soldiers Go, 1848’ for their recent charity CD.

Grehan’s bar was thought of as a kind of social centre, a

gathering house for musicians and singers. One of their frequent guests

was singer/songwriter and multi-instrumentalist John Hoban who says, “Helen

was the key to it. She had this massive understanding and deep empathy.

She had her own way of playing music that came from herself, the old

way. Nobody showed her anything. She simply played the guitar how she

thought it should sound”.

Any perceptive reader would have to agree with the words of Editor, by Jessamine O’Connor.

“I have read and re-read countless times these poems and songs, and

each time feel something new, learn something more. It takes real

courage to write and perform songs about vulnerable and exploited rural

girls, abandoned wives, or aging and destitute local men, while living

in rural Ireland. This courage is Helen’s greatest gift. This gift,

combined with fierce intelligence and literary skill, added to a

humanistic sense of duty, is what makes Helen’s work so outstanding.”

With her poet’s hat on, she uses the most sensitive writing

to explain, without judgment, how sometimes people can end up where they

never intended. How they can become twisted by life’s journey. She

brings the reader into those men’s minds and hearts; As the collection

implies Helen writes of returned Irish ‘navvies’ with complete

understanding.

She brings the reader into these men’s minds and hearts. She neither

patronizes nor excuses them.

If you ever, for want of employment in Ireland, ended up in

Camden Town or Cricklewwod this is the book for you. Or if a member of

your family took that journey and returned . . . or didn’t, don’t miss

it.

I‘ll give you just a taste of Helen’s insight in the last stanza of

Well at least their futures have peace,

have certainty beneath the clay,

the weighty earth, the dirt that made them

and broke them,

throwing it well back

full whack

when men were men and Paddy ruled rude

|

|

* * * * *

Bloomsday is on June 16th. Who Killed James Joyce is one of Patrick Kavanagh’s lesser-known poems.

Here are the words; I made a recording of yours truly attempting to read it. But the wav file doesn't work well.

I, said the commentator,

I killed James Joyce

For my graduation.

What weapon was used

To slay mighty Ulysses?

The weapon that was used

Was a Harvard thesis.

How did you bury Joyce?

In a broadcast Symposium.

That’s how we buried Joyce

To a tuneful encomium.

Who carried the coffin out?

Six Dublin codgers

Led into Langham Place

By W. R. Rodgers.

Who said the burial prayers? –

Please do not hurt me –

Joyce was no Protestant,

Surely not Bertie?

Who killed Finnegan?

I, said a Yale-man,

I was the man who made

The corpse for the wake man.

And did you get high marks,

The Ph.D.?

I got the B.Litt.

And my master’s degree.

Did you get money

For your Joycean knowledge?

I got a scholarship

To Trinity College.

I made the pilgrimage

In the Bloomsday swelter

From the Martello Tower

To the cabby’s shelter.

No comments:

Post a Comment