The Arnold Family - England to America

A Patriot and A Traitor – Cousins

Last month, we began the exploration of Benedict

Arnold’s military career – one that led both to great admiration from

General George Washington and to eventual disgrace as America’s most

infamous traitors. This month we shall attempt to understand the forces

at play in his life. We shall also trace the distant relationship of

Benedict Arnold to our family. Through his Westcott ancestral line, we

may ultimately find a closer relationship than now known.

MILITARY CAREER, cont.:

In his first outing in command of troops in March of

1775, Benedict, as Captain, commanded a unit tasked to gain control of

Fort Ticonderoga. Although successful, we find our young Benedict was

frustrated after losing his personal battle with Ethan Allen who had

marched from Massachusetts with his rowdy troop of Green Mountain Boys.

This was a militia unit formed in the 1760’s in a back area bounded by

the British provinces of New York and New Hampshire, an area which would

later become the State of Vermont. It was a family affair with units

commanded by Ethan and by members of his extended family. The troops

held deep ties and loyalty to Ethan Allen’s family and to him,

personally.

“Arnold was surprised and a

little angered because Ethan Allen did not care if Arnold had

permission from the Committee of Safety and Arnold couldn't talk Allen

out of relinquishing command. Arnold had to concede to accompanying

Allen and his rowdy, rough and tumble fighters. On May 10, 1775, they

surprised the British garrison and the Green Mountain Boys celebrated by

invading the rum stores of the British and getting totally sloshed.

They virtually ignored Benedict Arnold except when they were teasing and

jeering him. Arnold had an argument with Colonel James Easton, who was

to deliver the missive announcing the victory of the capture to

Massachusetts. In his regimental memorandum book, Arnold wrote:

“I took the liberty of breaking his

head, and on his refusing to draw like a gentleman, he having a hanger

[short sword] by his side and a case of loaded pistols in his pocket. I

kicked him very heartily and ordered him from the Point immediately.”

(SOURCE: http://www.ushistory.org/valleyforge/served/arnold.html)

The enmity between Ethan Allen, his related commanders,

and Colonel James Easton was but one festering wound upon Benedict

Arnold’s soul. He may have found quick satisfaction in manhandling

Colonel Easton, but that was short-lived. The two strong-willed and

bullheaded men, Allen and Arnold, would begin planning the first assault

on British troops garrisoned in Canada. Meanwhile, Fort Ticonderoga was

being held by their dual command.

“Easton returned from his

mission to Massachusetts while Arnold and Allen were planning the

Canadian Invasion. Easton had done his best to diminish Arnold's

participation in the capture of Ticonderoga and the two were arguing

once more. The hot-tempered Arnold soon had some more people to fight

with: Connecticut governor Johnathan Trumbull appointed Colonel Benjamin

Hinman to command the Fort. Ethan Allen relinquished his command.

Arnold did not, instead threatening to sail two ships under his command

directly to a nearby British outpost and surrender them. Hinman then

enlisted the treasonous Arnold's soldiers, took command of his ships,

and dissolved his command. Completely affronted, Arnold went to Albany

and there sent off a statement of the situation at Ticonderoga to the

Continental Congress.

“Arnold had been caught in

the middle of the political machinations of Connecticut and

Massachusetts, both vying for the glory that would accompany the capture

of the British stores at Fort Ticonderoga. When Massachusetts

acquiesced to Connecticut's preeminence in the territory, Arnold most

certainly felt abandoned.”

(SOURCE: http://www.ushistory.org/valleyforge/served/arnold.html)

Here we witness the first evidence of Benedict Arnold’s

thought process which would presage his ultimate treasonous acts. In a

fit of pique, rather than think calmly and enlist the aid of those who

actually respected and supported him, he rashly threatened an act

certain to bring down wrath upon him.

We now know that upon returning home, Benedict would

learn of the death of his young wife. Coupled with the anger still

fomented by his embarrassing and frustrating confrontation following his

successful taking of Fort Ticonderoga, was the anguish of his deep

personal loss, topped by the inability of the Continental Army to

remunerate him properly for his personal expenditures in support of the

cause. The Massachusetts Committee of Safety repaid him only a small

portion of his total bill, nowhere near the total. It would be some time

before he was fully recompensed.

The Siege of Montreal:

General George Washington had been much impressed by

Benedict Arnold’s daring actions and saw value where others merely saw

arrogance. He let it be known he wanted Benedict to take a commanding

role in the campaign which would be led by Gen. Philip Schuyler.

Benedict’s long years of trade with the Quebecois made his knowledge of

the people and the terrain valuable. In advance of the trek Benedict

Arnold sought to gain some knowledge from a long-time acquaintance, John

Dyer Mercier. Mercier made a most unfortunate decision. He handed off

Benedict’s letter to two Abenaki tribesmen who were in concert with John

Hall, a French-speaking British deserter. Somehow that letter fell into

the hands of the British command who, now alerted to the impending

invasion, had time to buttress their garrison. The entire campaign

seemed fated from the start. Of the 1,100 troops marched northward by

Arnold, only 600 made the trip due to the horrific cold of the winter,

disease, and starvation. Upon arrival, they found a much larger defense

amassed in advance. The weather also did not help. Rain poured down upon

the troops, a cold and chilling rain. Montgomery was killed, Benedict

suffered his first leg wound, and Daniel Morgan was called upon to

salvage what he could of the effort. In spite of Morgan’s heroic

efforts, the Americans were ultimately forced to surrender. From his

sickbed, Benedict refused to surrender – “bellowing commands” to his

troops, not merely reluctant but determined not to leave absent triumph.

It was to no avail, but word of his actions reached Washington who

marked this up in his favor as well. Washington named Benedict Arnold

the rank of Brigadier General.

We touched upon the rough and tumble nature of Benedict

Arnold’s character in last month’s column. Here again that came to the

forefront:

“Arnold became involved in

a dispute with Moses Hazen, an officer under his command, whom he

accused of insubordination for failing to carry out Arnold's orders to

seize supplies from Merchants in Montreal during the American army's

retreat. Hazen issued counter-charges against Arnold for issuing the

order to plunder in the first place. Hazen was acquitted at his

court-martial, and Arnold was ordered to apologize, an order he

indignantly refused. General Horatio Gates intervened on behalf of

Arnold, who was given charge of a small fleet of ships and ordered to

Ticonderoga.”

Benedict Arnold was mounting up enemies among the

officers with whom he would be tasked to fight the cause of America’s

revolution. The very attributes which made him a strong commander in

battle were negative faults in his personal interactions. These feuds

would cost him a most desirable promotion to Major General. While he

defended multiple complaints brought by his peers and senior officers,

Benedict watched junior officers being promoted ahead of him to Major

General. He was embittered. Once again, his admirer and defender,

General George Washington, would intervene behind the scenes to

investigate why he had not been consulted in connection with the

promotions handed out by Congress.

This promotion, however, was granted without the

seniority both Washington and Arnold felt he deserved. He would be

standing in an inferior capacity to many junior officers who served

under his command previously. He sent a letter of resignation to

Washington. Washington, unbeknownst to Arnold, was working behind the

scenes to secure a position of command on a second Siege of Montreal. He

refused Arnold’s resignation, instead placing him in a substantial role

in the second Siege of Montreal.

In a letter to John Hancock in Congress, Washington defended Arnold thusly:

“If General Arnold has

settled his Affairs & can be spared from Philadelphia, I would

recommend him for this business & that he should immediately set out

for the Northern department. He is active-judicious & brave, and an

Officer in whom the Militia will repose great confidence. Besides this,

he is well acquainted with that Country and with the Routs and most

important passes and defiles in it. I do not think he can render more

signal services or be more usefully employed at this time than in this

way-I am persuaded his presence & activity will animate the Militia

greatly & spur them on to a becoming conduct. I could wish him to be

engaged in a more agreeable service-to be with better Troops, but

circumstances call for his exertions in this way, and I have no doubt of

his adding much to the Honors he has already acquired.”

When he learned of this

opportunity, Arnold asked to put his resignation on hold. He immediately

took off for the north. On August 8, Congress voted not to reinstate

Arnold's seniority and he would never forgive them for the slight.

Arnold exhibited an innate strategic sense in battle.

He crossed horns with Generals Schuyler and Gates on more than one

occasion, even when his tactical plans were accepted and proven

successful. Again, the hostility he faced reared its ugly head when his

contributions to both strategic plans and tactical execution failed to

be mentioned in the official reports to Congress. He exhibited bravery

on more than one occasion, even when injured. These efforts failed to be

recognized by those whose disapprobation of him surmounted any level of

respect they might otherwise have felt.

Even after Gates relieved Arnold of his command for

insubordination, Arnold charged onto the field of battle astride his

horse, reinvigorating his troops and others at Bemis Heights. After

leading two separate onslaughts, Arnold along with Daniel Morgan’s

troops were able to push open the center of the British line, ensuring

ultimate success. In the final assault, Arnold’s horse was shot and it

fell upon the very leg Arnold had injured in prior battle. The bravado

of the Continental troops was so great, Burgoyne surrendered not ten

days later. Now, the French were willing to enter the fray in support of

the American rebel’s cause. Benedict

“Arnold’s actions, perhaps more than any other officer there, led to the American’s success.”

Even though Arnold’s seniority was later restored, the

damage had been done. He was now forever lame, had been discredited by

his superior officers, ignored by members of Congress, and was now a

widower with young children and felt the sting of being alone to raise

them. He returned home with enmity in his heart.

PERSONAL FACTORS:

While recuperating from his wounds at his home in

Philadelphia, 38 year old Benedict met and began wooing Margaret “Peggy”

Shippen, the youngest daughter of Judge Edward Shippen. A mere 18 years

of age, Peggy was vivacious, strong-willed, and deeply involved in the

Loyalist’s cause. They wed in April of 1779.

Peggy Shippen Arnold and daughter Sophia, by Daniel Gardner, circa 1787–1789.

The Shippen family was upper crust society, wealthy,

educated, and well respected. Arnold was once again thrust into a life

of social status, but without the means to support the lifestyle. He,

once again, resorted to the old street savvy ways. He engaged in real

estate speculation, a capital-intensive industry. In support of his

needs, Arnold began utilizing government assets as his own. He used his

position to approve the use of a ship and later invested in it in clear

contravention of propriety. He was brought up on charges and

court-martialed in June of 1779.

By this time, he had already begun negotiating with the

British to sell military secrets and to use his position to weaken the

defenses of West Point. He had been given command in spite of his peer’s

opposition. Now he bartered that command for filthy lucre! Through the

intermediary Major John Andre, a friend and possible former lover of

now wife Peggy Shippen Arnold, Benedict funneled information to the

British in return for money. He even gave vital information on the

movements of his old mentor George Washington.

In a letter dated 12 July 1780, directed to Major John

Andre and Sir Henry Clinton, Benedict outlined critical information

about American troop movements, specifically a plan of disinformation

revealed to Benedict by his old friend and trusting mentor, George

Washington. Benedict shamelessly betrayed Washington, providing full and

complete information that could have brought death to General

Washington. In the letter, he also revealed this was not the first

information provided the Brits for money. He apparently reiterated his

prior betrayals as a reminder of his monetary value to them. In the

final paragraphs of that letter, Arnold reveals his motivations and

belief as to the ultimate failure of the Revolutionary cause:

“He disclosed his general

feeling about the impact of the war on American resolve and morale. He

thought that Americans were tired of the war and would give up soon if

they did not see any substantial benefit. He thought that the last few

struggles were futile and showed American weakness and discouragement.

Furthermore, Arnold again emphasized that he expected substantial and

urgent payment for his services.”

(SOURCE: http://clements.umich.edu/exhibits/online/spies/stories-arnold-2.html)

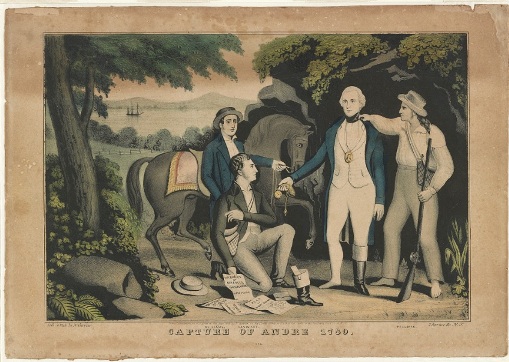

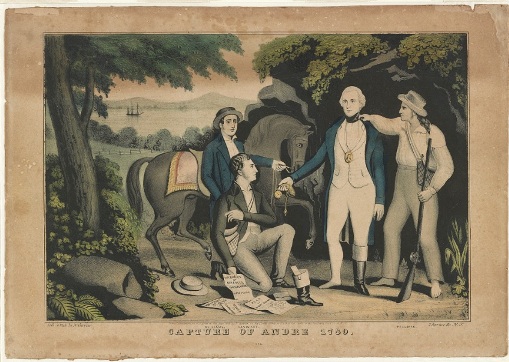

A portrait of the Capture of Major John Andre, British spy

A portrait of the Capture of Major John Andre, British spy

When Benedict Arnold learned of the capture of Major John

Andre and the discovery of his betrayal, he escaped aboard the very ship

that had brought Andre to American shores, the Vulture. His betrayal

must have brought to Benedict the ultimate sting of defeat. As reported

by US History.org (see Source information above):

“Arnold defected to the

British and received substantial remuneration for his defection. These

included pay, land in Canada, pensions for himself, his wife and his

children (five surviving from Peggy and three from his first marriage to

Margaret) and a military commission as a British Provincial brigadier

general.

The British provided

handsomely for Arnold, but never completely trusted him. He was never

given an important military command. They moved to London where he found

no job, some admiration and even some contempt. He moved his family to

Canada where he reentered the shipping business. The Tories there

disliked him and had no use for him, and eventually he returned his

family to London. When the fighting began between France and England, he

tried again for military service, but to no avail. His shipping

ventures eventually failed and he died in 1801, virtually unknown, his

wife joining him in death three years later.”

OUR RELATIONSHIP TO BENEDICT ARNOLD:

Gen. Benedict Arnold V, The Traitor (1740 - 1801)2nd great-nephew of husband of 8th great-aunt

Benedict Arnold III (1683 - 1761)Father of Gen. Benedict Arnold V, The Traitor

Benedict Arnold II (1641 - 1727)Father of Benedict Arnold III

Damaris Westcott (Arnold) (1620 - 1679)Mother of Benedict Arnold II

Stukely Westcott (1592 - 1677)Father of Damaris Westcott (Arnold)

Jeremiah Westcott (1633 - 1686)Son of Stukely Westcott

Eleanor England (Westcott)(1643 - 1692)Wife of Jeremiah Westcott

Hugh Parsons (1612 - 1684)Father of Eleanor England (Westcott)

Hannah Parsons (1646 - 1685)Daughter of Hugh Parsons

Thomas Matteson (1673 - 1739)Son of Hannah Parsons

Mary Matteson (1651 - 1701)Daughter of Thomas Matteson

William (of Deerfield) Joslin Col. (1701 - 1771)Son of Mary Matteson

William "P.R." Joslin (1757 - 1846)Son of William (of Deerfield) Joslin Col.

William (James) Riley Joslin (1792 - 1871)Son of William "P.R." Joslin

William Henry Joslin (1837 - 1921)Son of William (James) Riley Joslin

James Arthur Joslin (1874 - 1956)Son of William Henry Joslin

Lena May Joslin (1918 - 2010)Daughter of James Arthur Joslin

Your author and her siblings - the four Daughters of Lena May Joslin

Carroll.

Interestingly, our relationship to General Benedict Arnold

V, the Traitor, may be closer. By DNA testing, we discovered our

maternal uncle on the Joslin line had his closest match to one Westcott

Campbell Joslin, Sr. Your author is still researching that line to

determine our Shared Ancestor and, perhaps, break down the brick wall

that still exists between William “P.R.” Joslin and the Colonel William

(of Deerfield) Joslin. For it is our belief that P. R. was the grandson,

not the son. When and if we chip away successfully at that wall, it is

believed the Shared Ancestor with Westcott Campbell Joslin will provide

the parental line that is missing – that ONE generation. Clearly,

Westcott was named for his Westcott relatives, but we have yet to

ascertain exactly how that interrelates to our line.

Next month, we cover the Arnold Family – the heroes.

That line intersects directly with my husband’s, Rod Cohenour. It should

be interesting!

Click on author's byline for bio and list of other works published by Pencil Stubs Online.