A Remarkable Life – The Story of

Ruth Margaret Muskrat Bronson

Born: 3 October 1897, Grove, Indian Territory (now Oklahoma)

Died: 12 June 1982, Tucson, Pima County, Arizona

The story of Ruth Margaret Muskrat Bronson is intertwined

with the history of the Indian Territory where she was born. Her

heritage – the land where she was born and its history – inspired her

life’s work. The Indian Territory was an area of land known by a number

of differing titles as its use and various Acts of Congress as well as

treaties affected its boundaries, the laws governing its use, and the

indigenous peoples of our country who would become its inhabitants.

History of the Indian Territory, in part:

The land encompassing the Indian Territory was originally a

much larger tract of land “the British government set aside for

indigenous tribes between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi

River in the time before the American Revolutionary War.” (SOURCE:

https//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_Territory)

Use of this area of land mirrored the concept of aboriginal

peoples who were present in America at the time of European immigration

and for thousands of years preceding that time as being “savages” or

“barbarians” incapable of governing themselves, a danger to all

settlers, and a scourge to be wiped out or, at minimum, isolated,

defanged, and tightly controlled. Thus, these Native Americans were

systematically ill treated by colonists and their governing countries,

their land routinely taken from them by negotiating treaties (that were

never honored), and their peoples prompted to move from their

traditional homelands to the as yet unpopulated or sparsely populated

territory “out West.”

After the Revolutionary War, the newly formed United

States dealt with the Native Americans in varying ways – dependent upon

the allegiances shown by each tribe during that war. Those who aligned

themselves with the Brits became the target of vengeance. However, those

tribes who had fought alongside the rebellious colonists were,

likewise, mistreated. For, in fact, few of the European immigrants were

willing to permit the indigenous tribes to continue life as usual.

The solution for the problem of “how to deal with the

Indians” became that of “Indian Removal” – the systematic stripping of

each tribe’s land, their farms, livestock, and goods and various means

of forcing their removal to the Indian Territory. The United States took

control of the ownership of lands by legislating the need for

governmental approval of any sale thereof. From the time of the

Revolution until 1834, this was accomplished by Acts of Congress. Five

such Acts were passed between 1790 and 1802, and then the almost

identically worded Act passed in 1834:

The 1834 Act, currently codified at 25 U.S.C. § 177,

provides:

No purchase, grant, lease, or other conveyance of land, or of any title

or claim thereto, from any Indian nation or tribe of Indians, shall be

of any validity in law or equity, unless the same be made by treaty or

convention entered into pursuant to the constitution.

The first of these Acts passed in 1790 prompted this

promise from President George Washington to the Seneca Nation of New

York:

“I am not uninformed that the six Nations have been led

into some difficulties with respect to the sale of their lands since the

peace. But I must inform you that these evils arose before the present

government of the United States was established, when the separate

States and individuals under their authority, undertook to treat with

the Indian tribes respecting the sale of their lands. But the case is

now entirely altered. The general Government only has the power, to

treat with the Indian Nations, and any treaty formed and held without

its authority will not be binding. Here then is the security for the

remainder of your lands. No State nor person can purchase your lands,

unless at some public treaty held under the authority of the United

States. The general government will never consent to your being

defrauded. But it will protect you in all your just rights.”

This promise, as would almost every single future assurance

by the United States government to the various tribes of Native

Americans, would not be honored.

Ruth Margaret Muskrat Bronson’s family history:

Ruth Muskrat was the fourth child of seven children,

and second daughter of four daughters of James Ezekiel Muskrat (b. 2 Jul

1856, Delaware District, Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory and d. 15

Jun 1944, Grove, Delaware County, Oklahoma, United States) and his wife

Ida Lenore Kelly (b. 31 Mar 1870, Vernon County, Missouri and d. 23 Jun

1956, Grove, Delaware County, Oklahoma). Of this union, the seven

children were: Maud Dorcas Elizabeth “Maudie” (1890-1970); Jacob Claude

“Jake” (1892-1939); Harvey Robert (1895-1980); Ruth Margaret

(1897-1982); Ruby Jewel (1900-1987); Thelma (1902-2005); and Truman

(1904-1907).

Photograph of James Ezekiel Muskrat and wife Ida Lenora Kelly Muskrat, taken about 1887.

Ruth’s great-great-grandfather was known as Wa-sa-tee or

Wu-so-di, also called Muskrat (Muskrat, in the original Cherokee or

Tsalagi syllabary created by Sequoia, was spelled se-la-gi-s-qua or

se-la-qui-s-gi). He is believed to have been born in the lands of the

Eastern Cherokee, now known as the State of Georgia. When gold was

discovered on the lands occupied by the Eastern Cherokee, there was

immediately a move to take the land and cheat the Cherokee of what was

rightfully theirs. Thus, the forcible removal of all households known by

various Census enumerations to be headed by a Native American male,

whether or not the wife was Cherokee or White. (Interestingly, those

households headed by White males with Cherokee wives and mixed blood

children were permitted to stay; thus, forming the initial population of

the Eastern Cherokee.

This event would have long-lasting repercussions for

the Cherokee. The disagreement as to strategic planning that arose

between tribal members faced with the prospect of being forced from

their tribal lands led, eventually, to an internal civil war and the

Muskrat families were right in the midst of it all.

On one of the many Indian census enumeration that

occurred through the decades, the Drennen Roll taken 1851, the family of

Jackson Muskrat (Group number 131, former Dawes family identification

number 4270), appears on the same page, opposite column as the family of

the very famous Cherokee, Stand Watie, (Group number 123.) For those

steeped in Cherokee history, the name of Stand Watie signals the stuff

of legends, along with such names as John Ross and Ned Christie.

Stand Watie and John Ross supported opposing strategies

for dealing with the United States government’s intent to forcibly

remove the Eastern Cherokee from their homes. Watie felt it was

expedient to negotiate and secure treaty considerations that would

provide legal standing for the tribe. John Ross wished to refuse to

negotiate and confront the government forces directly. Ultimately, many

of the Cherokee families sided with Watie and ceded their lands (the

Treaty of New Echota signed in 1835). They were paid ridiculously small

amounts and the future considerations failed to equal the value of the

properties ceded. This resulted in a split in the tribe and lingering

hatred. Those Cherokee who sided with John Ross refused to ratify the

Treaty. Watie and his group removed peaceably to the Indian Territory,

joining with those who had relocated in 1820 (known as the “Old

Settlers”). In 1838, the government forcibly removed those remaining in a

journey fraught with horrors, known as the “Trail of Tears.” This group

of Cherokee were forced from their homes and permitted to take only a

few items of their household treasures with them. Their farms, homes,

barns, livestock, household goods, monies were left behind. They were

forced to walk without regard for their age (very young or very old),

their health, or their abilities. They were provided inadequate food and

water and no suitable cold weather gear. Many starved, froze to death,

or fell prey to fatal illness. More than 4,000 died.

In 1839, a group of those opposing the Treaty mounted

an assassination attempt and managed to kill all the leaders who

supported the Treaty except for Stand Watie. In 1842, Stand encountered

one of the men who had killed his uncle. Watie killed him. In 1845,

Stand’s brother Thomas was killed in retaliation. (SOURCE:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stand_Watie)

The Civil War renewed the festering hostilities when

Stand Watie joined the Confederacy and John Ross fought with the Union.

(Stand Watie was one of only two Native Americans to attain the rank of

General during that war, and he was the only Native American Brigadier

General.) Post-War, the government was faced with a request by Stand

Watie, who had served as Principal Chief during the hostilities, to

affirm his position and work to mend peacefully the fracture between the

warring Cherokee factions. The government chose to support John Ross

since he had fought for the Union. Watie was defeated, Ross was named

Principal Chief, and the controversies merely lay dormant and not

finally settled.

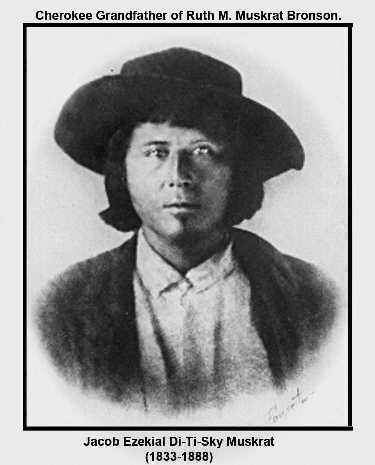

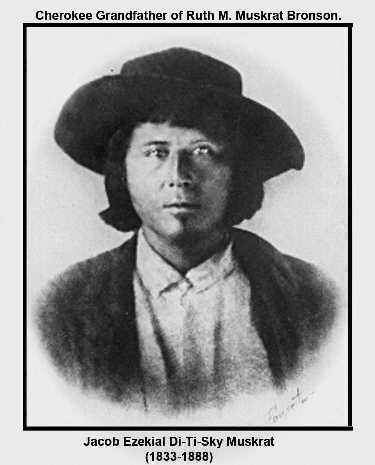

Ruth Muskrat Bronson’s grandfather, Jacob Ezekiel Muskrat, fought with Stand Watie’s Confederate troops.

(U. S. Confederate Service Records, 1861-1865: Name: J Muskrat

Military Unit: First Cherokee Mounted Volunteers (Watie's Regiment,

Cherokee Mounted Volunteers; 2d Regiment, Cherokee Mounted Rifles,

Arkansas; 1st Regiment, Cherokee Mounted Rifles or Riflemen)

Jacob Ezekiel “Di-ti-sky” Muskrat, in Confederate

uniform.] Ruth's great grandfather fought in Stand Watie's Confederate

regiment. First Cherokee Mounted Volunteers (Watie's Regiment, Cherokee

Mounted Volunteers; 2d Regiment, Cherokee Mounted Rifles, Arkansas; 1st

Regiment, Cherokee Mounted Rifles or Riflemen

Ruth Muskrat Bronson’s Personal History:

Ruth was born in White Water, Delaware District, Indian

Territory (now Grove, Delaware County, Oklahoma) on 3 October 1897. The

1900 US Census for District 0016, Township 24, Cherokee Nation, Indian

Territory shows Ruth’s father to be farming, born in Indian Territory,

her mother keeping house and born in Missouri. Her younger sister Ruby

just four months of age.

The next Census, enumerated 1st September 1902 was one

of the routine Native American Enrollments which documented her to be

“Cherokee by blood,” Census Card number 4137, and assigned Dawes roll

number 24438.

Ruth was fortunate in being born in the Cherokee Nation

for this tribe valued education. The elders, recognizing the value of

the missionary schools established in the 1820’s, wrote into their

Constitution the funding and organization of a school system. According

to the website

http://www.cityofgroveok.gov/community/page/city-grove-history:

“By 1845, the Cherokee National Council had three Indian schools operating in the Delaware District.”

The first public school was built in 1904. Every few

years the town’s council managed to add to the school and improve its

facilities. This provided an excellent grounding in the basics: math,

English, literature, an introduction to the arts, and fuel for the

hungry and eager mind of Ruth Muskrat! For Ruth was geared to learn, to

achieve, to improve, and to hone her skills.

By 1911, her elementary, middle and high school

education had been completed successfully and Ruth had moved on to her

first level of higher education. At age fourteen, she was an avid and

popular student at the University Preparatory School at Tonkawa,

Oklahoma. In 1916, Ruth took first prize in the Poetry Contest with a

poem that would speak to the love she held for her tribe:

The Warrior’s Dance

Ruth Muskrat, ‘17

First Prize in Poetry Contest

With the droning hum

Of the low tom-tom,

And the steady beat of the many feet,

With the wild weird cry

Of the owl nearby

Came the night of the warrior’s dance.

With dark bronze faces,

And gorgeous laces,

With body straight and stately gait,

With black hair streaming,

And black eyes gleaming,

Came the warriors to the dance.

The moonlight beams,

The camp fire gleams,

The tall trees sigh as the wind rushes by;

The squaws smile in pride.

At their slow solemn stride,

As the warriors march in the dance.

There is happiness there,

Joy fills the air,

They have forgot their hapless lot,

They are kings once more,

As in days of yore,

As they swing to the warriors dance.

Another of her literary efforts was an ode to the new

State of Oklahoma, which she entitled, “Oklahoma as a Background for

Literature.” This essay speaks of her love of the land, its diversity of

topography, wildlife, the numerous waterways – lakes, creeks, and

streams – and the inspiration this beauty provides to writers. One can

get lost merely researching this young woman’s literary works; for at

the young age of nineteen, Ruth had already found her voice.

Ruth had a well-rounded personality. Her school record

is filled with her achievements: poetess, author, Vice-President of her

YWCA and an active member involved in donating Christmas gifts to needy

children, traveling as a delegate to assist in formulating activities

and the direction for the organization in the following year. She also

served as President of the Sorosis sorority in the same year.

Through her work for the Young Women’s Christian

Association, Ruth was chosen to spend a summer working with Mescalero

Apache youth in New Mexico. She had two years’ student teaching under

her belt by this time and was a vocal and enthusiastic advocate for not

merely memorializing the native culture, but a devotion to nurturing and

maintaining that culture in a harmonious blend with modern ways. This

would become Ruth’s life’s work: advocacy for the rights of Indians to

be Indians, yet to become flexible and knowledgeable of every advance in

education, philosophy, or methodology in all aspects of life.

Having exhibited her ability to absorb knowledge and

utilize that knowledge in innovative ways, Ruth received a scholarship

for the University of Kansas, where she attended for three semesters,

before accepting a scholarship for the University of Oklahoma. At

Lawrence, she was a member of the Pen and Scroll Club, a literary

organization. Her time at university was well spent. She forged ahead,

hungry for more knowledge and solidifying her philosophy concerning her

beloved Indian culture. Ruth’s successes with the Apache youth prompted

the YWCA to select her in the Fall of 1922 to be their envoy and

representative of the North American Indian at a conference held in

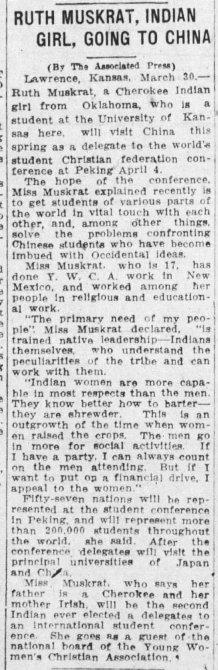

Peiping, China.

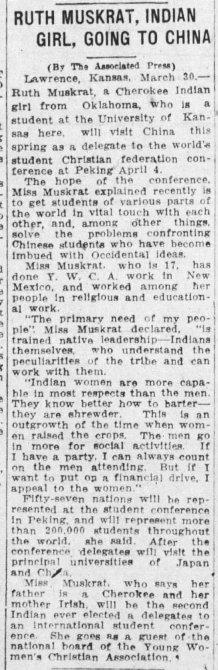

Ruth Muskrat Bronson - AP News article re Trip to China for YWCA 31 Mar 1922, p5-1

Upon her return from China, she was granted yet another

scholarship – this time to Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley,

Massachusetts, which she attended from 1923 until her graduation in

1925. She is recognized as one of the school’s most honored and

distinguished alumna. From the book, Heritage of the Hills – A Delaware

County History, comes the following:

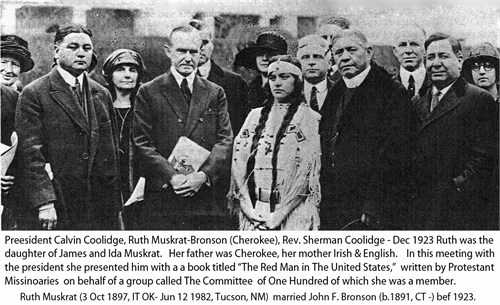

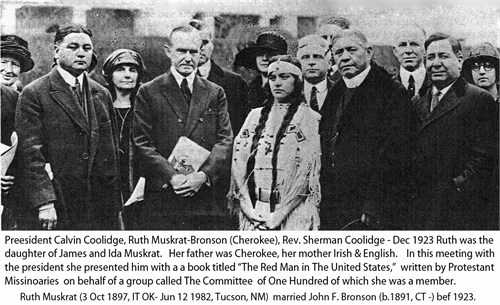

During her junior year at Mount Holyoke, she was chosen to

present President Coolidge with a copy of a book entitled "The Red Man

in the United States" by G.E. Lindquist. The book is the story of the

Red Man's struggles, tragedies, victories and developments. The beaded

book cover symbolizes the story of the old type Indian and the new. It

was beaded by a Cheyenne woman Na-Nah-Na whose name means Fish Woman.

The buckskin costume Ruth wore was fashioned by Fish Woman in Oklahoma

under the direction of Rose Kincaide, Supertintendent of Mohonn Lodge at

Colony, established to encourage Indian crafts. Alice Antelope made the

beaded moccasins. Alice Lester, a Mescalero-Apache, wove the head band.

There was also a book mark made of tiny arrowheads, a proud gift of Jim

Wilson of Tahlequah.

The presentation was made

with such force and clarity that the Chief Executive invited her to take

lunch with him and Mrs. Coolidge.

Mount Holyoke chose to honor Ruth in 2016 as one of their

most competent alumna, one who best utilized the knowledge and skills

gained through her time at that institution of learning. The following

excerpt was published on their website and may best verbalize one of

Ruth’s crowning achievements:

For the upcoming Indigenous Peoples Day, the Archives and

Special Collections has decided to feature Ruth Muskrat, a Cherokee

Indian-Irish student from the class of 1925. (An excerpt):

At the age of ten, she witnessed an Oklahoma statehood

movement that dissolved Cherokee national institutions, divided up the

Cherokee estate, and replaced Cherokee citizenship with United States

citizenship. This experience would solidify her philosophy of Indian

cultural survival–she insisted that American Indians had a legitimate,

legal claim to both a tribal identity and an American identity. She

strongly believed in cultivating a new generation of Indian leaders and

that viable solutions to Indian problems could only be found by Indians

themselves. She presented her philosophy of Indian leadership to a

prominent Committee of Indian rights activists known as the Committee of

One Hundred during their meeting with President Calvin Coolidge in

1923. (SOURCE: Mount Holyoke College archives:

http://mhc-asc.tumblr.com/)

Portrait of Ruth Muskrat in Cherokee Indian attire: Five College Compass Digital Collections: circa 1923-1925

From Wikipedia:

The

trip, which also included stops in "Hawaii, Manchuria, Japan, Korea and

Hong Kong" brought Muskrat to the attention of the international press

and awoke in her a desire for racial equality. The following year, she

delivered an appeal to the United States government for better

educational facilities for Native Americans. The presentation was part

of a gathering of Native American leaders, known as the "Committee of

One Hundred" to advise the president on American Indian policy. Muskrat

advocated for Indians to be involved in solving their own problems.

Moved by her speech, President Calvin Coolidge and his wife, Grace,

invited Muskrat to lunch with them.

President Calvin Coolidge presented with a book written by

G. E. E. Linquist titled “The Red Man In The United States” (1919). Ruth

Muskrat Bronson (center) making the presentation to President Calvin

Coolidge on behalf of “The Committee of One Hundred” with Rev. Sherman

Coolidge (right), December, 1923. // Credit: Public Domain

RuthwPresidentCalvinCoolidge-Dec-1923

Ruth Muskrat with President Calvin Coolidge Dec 1923

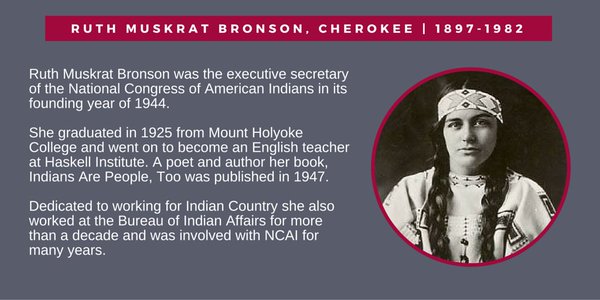

Upon graduation from Mount Holyoke, Ruth accepted a

position at Haskell Indian Institute in Lawrence, where she taught

English and Literature and served one year as Registrar.

At the end of her first year there, she was awarded the Henry G.

Morgenthau $1,000 award for the senior who had accomplished the most

their first year out of college. (SOURCE: Heritage of the Hills, ibid)

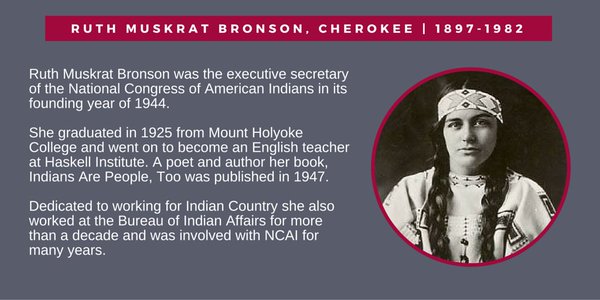

Ruth’s distinguished career is detailed in Wikipedia.

It is the summation of this remarkable woman’s remarkable life: After

marrying John F. Bronson in 1928, they adopted a native girl. This is

the only child of their union. Ruth continued to be active in her

career, steadily gaining more recognition for her outstanding talents

and her passion for the causes she championed. When the Bureau of Indian

Affairs (BIA) created a new program “to improve educational

opportunities for Native Americans,” Bronson was appointed its first

Guidance and Placement Officer. From 1931 to 1943, Ruth served in this

capacity at the BIA. During her tenure she received numerous awards. In

1937, the Indian Achievement Medal of the Indian Council Fire, first

nominated for the award in its inaugural year (1933), she was only the

second woman to receive the award.

"Ruth Muskrat, ’25. Holyoke alumna who has been

appointed as a Guidance and Placement Officer on the Bureau of Indian

Affairs with a territory of eight mid-West states."

Along with the numerous poems published by Ruth, she also

wrote and published a number of books and articles, including her most

famous Indians are People Too (1944), The Church in Indian Life (1945)

and Shall We Repeat Indian History in Alaska? (1947).

Ruth Muskrat Bronson - 1947

From Wikipedia:

“In

1945, Bronson began working with the National Congress of American

Indians (NCAI) and soon emerged as a leader. She was appointed as the

executive secretary of the organization and spent a decade monitoring

legislative issues. She established the NCAI's legislative news service

and spoke at various tribal meetings throughout the country, promoting

Native American progress. Some of the issues Bronson was involved with

at the NCAI were the debates over native water rights along the Colorado

River, native rights in the Territory of Alaska, and medical care for

American Indians. After ten years of serving as executive secretary, in

1955, Bronson was elected as treasurer of the NCAI , but she was

tired of the contentiousness of national politics and began focusing

more on ways to work with local communities.

Ruth Muskrat Bronson - Exec Secretary, National Congress of American Indians, founded 1944

In 1957, Bronson moved to Arizona and became a health

education specialist at the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation for the

Indian Health Service. During the same period, she served as a vice

president of the philanthropic ARROW Organization. She managed the

education loan and scholarship fund of the organization, as well as

advising tribes on community development. In 1962, Bronson was awarded

the Oveta Culp Hobby Service Award from the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare for her work serving Native Americans and retired

from government service, moving to Tucson. In 1963, Bronson became the

national program chairman of the Community Development Foundation’s

American Indian section. The organization operated under the umbrella of

the Save the Children Federation. After a stroke in 1972, Bronson

slowed, but did not stop her activism for Native Americans to be allowed

to determine their own development and leadership programs. In 1978,

Bronson was one of the recipients of the National Indian Child

Conference's merit award for commitment to improving children's quality

of life.”

On 12 June 1982, Ruth Margaret Muskrat Bronson departed

this life to return to the spiritual world of her ancestors. She was in a

nursing home in Tucson, Arizona, when she passed beyond the veil.

Newspapers around the world carried the news of this passionate

advocate’s death, one of them being The New York Times. A link for the

obituary published by The Times on 24 June 1982 follows:

http://www.nytimes.com/1982/06/24/obituaries/ruth-muskrat-bronson-84-a-specialist-in-indian-affairs.html

Researched and Compiled by Melinda Cohenour

Click on author's byline for bio and list of other works published by Pencil Stubs Online.