A Much Maligned Man: Sidney Washington Creek

Born: 13 January 1832 in Liberty, Clay County, Missouri

Died: 12 September 1892 in Liberty, Clay County, Missouri

Chapter 4 in the Life of the Much Maligned Man

In August of 1862, Missouri was fully embroiled in the

violence and unrest that had fomented the great and horrible Civil War

that would result in the greatest loss of life yet seen by Americans in

any armed conflict. Within the borders of Missouri and its neighboring

state of Kansas, factions were sharply divided and loyalties split

between the abolitionist views and the established lifestyles of the

Southern pioneers. Missouri’s Governor in 1861 was Claiborne Jackson, a

neutralist who discouraged enlistment of Missourians to Federal

service. In June of 1861 Federal authorities supported the formation of

Unionist Home Guard regiments Federally controlled; however, these

units were largely disbanded by the end of 1861 and replaced by

six-month service state controlled militia whose responsibilities were

severely limited and loosely managed. By January of 1862, these units

had also disbanded and been replaced by the Missouri State Militia, a

force of mostly cavalry units still state controlled.

As discussed in the previous installment of Sid Creek’s

story, the Red Legs of Kansas continued to organize deadly thieving

raids across the border of Northwestern Missouri. Almost all the hale

and hearty men folk were either engaged by the Confederate Army or had

enlisted as Union soldiers, leaving the farms and homesteads occupied

only by women, children and elderly men vulnerable to attack and

destruction. Those young men left behind oftimes joined with guerilla

forces to protect their homesteads and remaining family from those

vicious attacks.

Following the disastrous Battle of Pea Ridge,

Confederate forces had withdrawn from Northern Arkansas and flooded into

Missouri to recruit those loyal to the Southern cause. The success of

this recruiting effort, coupled with the failed state militia efforts to

date, resulted in Confederate Jefferson Davis choosing to legitimize

the burgeoning guerilla bands by encouraging them to “follow the rules

of war” and later be folded into the Confederate Army. This was not

acceptable, of course, to the Union Army and Brigadier General John

Schofield would respond by issuing Order No. 18 to the Missouri State

Militia which read, in part,

"When caught in arms, engaged in their unlawful warfare, they will be shot down upon the spot." (SOURCE: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enrolled_Missouri_Militia )

This Order, though strongly worded, had little effect

given the dwindling forces of the Missouri

State Militia and the success of the Confederate recruitment efforts.

In a move to counter these issues, on 22 July 1862 Schofield, aided by

the provisional Governor, Hamilton Rowan Gamble (who had served 4 Mar

1822 as circuit attorney in the trial where Sidney’s grandfather,

Abraham Creek, served as a juror), issued an order requiring compulsory

enrollment.

General Order No.

19 requiring loyal men to enroll in the militia, required registration

of all who had previously taken up arms against the United States, and

for them to surrender their weapons. The disloyal and Confederate

sympathizers would not be required to enroll in the militia, but would

have to declare their sympathies, which many were unwilling to do and

instead enrolled.

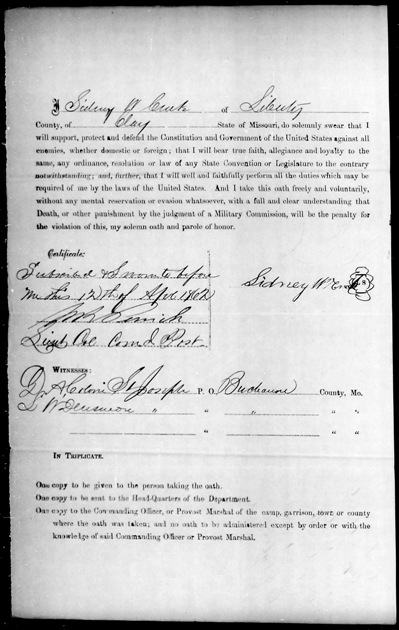

On 12 April 1862, Sidney Washington Creek, under duress,

signed the Oath of allegiance before Col. M. B. Pennick, Liberty

Missouri Command Post and gave bond.

1862-4-12 - Sidney Creek sworn oath to Pennick certificate

His allegiance, however, was definitely to the cause of the

Confederacy. As subsequent tightening of restrictions against Southern

sympathizers began to be exerted, Sid chose to make plans to protect his

family and serve according to his conscience. In early August of 1862,

he delivered his wife (Lucinda) and children (Georgia, Charles, Emma,

Lamira, and Beau) to the estate of his father-in-law, Henry H. Estes.

Estes would later, in a deposition prompted by the forfeiture of Sid’s

allegiance bond, state that he urged Sid to stay and not give up his

bond by leaving. Sid stated fervently that he “valued his life more than

property” and was “going to the bush.” Later that same month, Sid was

sworn into the Confederate service at Jackson, Missouri, enlisting for

“three years or the war” and was assigned to the Confederate 9th

Regiment, Missouri Cavalry, Company B (Elliott’s battalion, Capt.

Walton’s company).

The morning of 8 January 1863, would find Sid marching

with the Confederate troops assigned to Col. Joseph Orville Shelby on

the outskirts of Springfield, Missouri. The mission was to augment the

two regiments marching in under Brig Gen. John S. Marmaduke who was

driving forces up from Pocahontas and Lewisburg, Arkansas, into the area

where the Union forces per scout reports had been weakened. In this

series of skirmishes, Sid would bear arms. Timing became a critical

factor for the rebel troops, as columns commanded by Col. Joseph C.

Porter and Col. Emmett MacDonald failed to arrive in time to make a

coordinated pincer attack against the embedded Union troops. Ultimately,

the Confederate troops were forced to withdraw, suffering losses

greater than those of their Union counterparts.

Immediately following Marmaduke’s retreat from

Springfield, his troops met up with Col. Porter. They engaged Union

forces over three days (January 9 to 11, 1863) at Hartville, Missouri.

As part of Col. Ben Elliott’s 1st Bttn., Missouri Cavalry, under command

of Col. J. O. Shelby, Sidney Creek was assigned to picket duty. This

consisted of a fixed position scouting operation where the advance

location of the pickets could relay word of opposing forces’ movements

to their commanders, thus, directing the most opportune strategic moves

for the troops. This three-day operation resulted in mixed successes.

The Union forces were disrupted, forced to abandon some key positions

and permitted Marmaduke to set up a field hospital for a time; however,

the resultant loss of several Confederate leaders (among them Brigade

Commander Porter and Col. MacDonald) dealt a serious blow to the

Confederate troops.

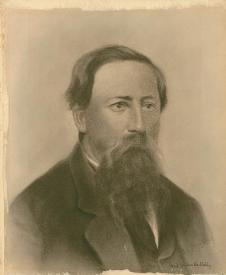

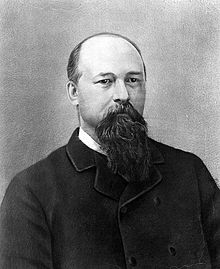

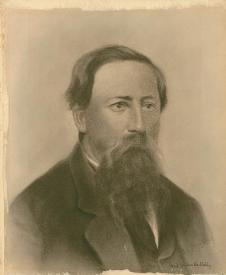

This is a charcoal sketch done by Anna Lee (Dillenbeck) Stacey.

Charcoal portrait of General Joseph Orville Shelby in suit coat, vest, shirt, and tie.

The drawing is signed by the artist. Below the signature,

"Genl. Jos. Orvill Shelby" is written in different hand

From State of Missouri website Archives covering the Civil War.

|

|

Following the days long skirmishes at Hartville,

Missouri, Marmaduke marched his troops back south to Arkansas. Sid, as

part of Col. Shelby’s command, was encamped south of the White River at

the farm of Franklin Desha. It was bitterly cold. Union Col. George

Waring, 4th Missouri Cavalry, along with his 600 troops was given

permission to engage the Confederate forces at Batesville, Arkansas. It

is reported that a CSA scout who rushed to Marmaduke to warn of the

impending foray was disbelieved. (Your author, given knowledge of Sidney

Creek’s canny abilities, recent duties as an advance scout, and family

lore that he served as a spy for the rebels, wonders if this scout was,

indeed, our Sid.) At any rate, many of the rebel troops managed to move

by ferry across the White River ahead of Waring’s approach. Knowing he

was badly outnumbered by the troops under Marmaduke’s command, Waring

employed a few slick tricks to delude his enemy as to the size of his

own command. He ordered small groups to deploy over a wide area, setting

up fake campfires to indicate a wide-ranging group of men. He also

employed misinformation techniques by use of the local rumor mill,

dropping hints that his was merely a small detachment of a much larger

force soon to arrive. This strategy served to deter Marmaduke from

crossing back over the river and engaging the much smaller force with

his some 3,000 plus soldiers. Early the following morning, 4 February

1863; however, Shelby gave chase.

The Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture (website) reports:

encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=6690

The Union

troops wasted no time packing and preparing to move at dawn; as Waring

reported: “We levied such contributions of supplies as were necessary

for our return march, and, in order that the return might not look like a

retreat, we loaded two wagons with hogsheads of sugar, which would be

welcome in Davidson’s commissariat.” Local resident Emily Weaver noted,

“Towards day-break, the whole command moved swiftly north, and a few

hours later, Gen. Shelby crossed the river with about three thousand

men, and followed them a short distance.”

Waring led his men, their prisoners, and their supplies as

rapidly as possible through the snow back north. One historian

summarized the end of the story succinctly. “The command then marched

to Evening Shade, Arkansas, twenty-five miles north of Batesville, where

Waring paroled and released most of his badly frostbitten prisoners.”

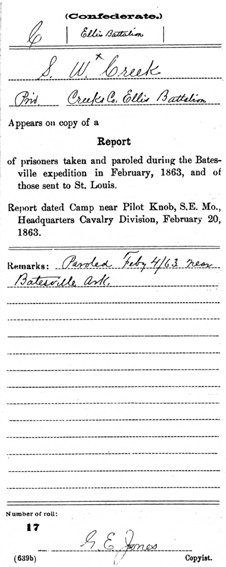

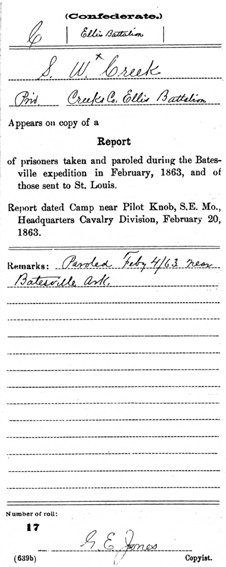

That February of 1863, Sidney Washington Creek became one of Gen. Waring’s unfortunate prisoners of war.

He was captured, and detailed to care for the sick and wounded.

The bitter cold, lack of food, exhaustion and ragged clothing had taken its toll.

Within a few days, Waring paroled his prisoners, partly to avoid having to care for them as well as his own troops.

|

|

Sid managed to find a sympathetic farmer who permitted him to

stay there, work the farm, rest up, heal and recover sufficiently to

start for home as soon as the weather broke. Spring finally brought

warmth for travel and on 20 May 1863, Sid set off, finally, for his

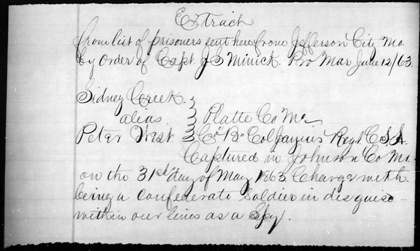

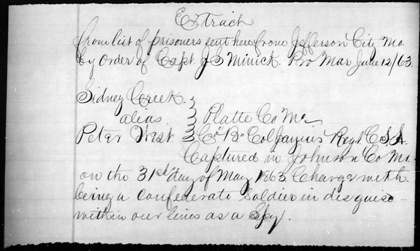

home. On 31st May 1863, Cyrus Peroman, a private with the EMM, spotted

him in Johnson County, Missouri. Sid was behind enemy lines, dressed in

the uniform of a Union soldier. He gave his name as Peter West, but was

soon identified as one Sidney Washington Creek, Confederate Spy.

|

|

Sidney Creek alias Peter West. |

Although your author believes the Provost Marshal

General took the statement of one “Peter West” extensive searching has

only turned up the cover used for the evidentiary file. We do, however,

have the statement provided under the true name of Sidney Creek:

“I was taken prisoner by

Col. Warren’s (*) forces near Batesville, Ark. about 6th day of Feb’y

1863, & was paroled. I remained in Arkansas from that time (working

on a farm) until about May 20th 1863 when I started for my home in Clay

Co. Mo. I was making my way through Johnson Co. when arrested. I got the

Federal Clothing I had on when arrested from a Confederate Soldier who

was arrested & paroled at the same time I was, & who afterwards

died. I think he got them at Springfield. I have no leave of absence or

furlough, but was coming home intending to deliver myself up to the

Federal authorities for trial for breaking my oath & bond. I was run

off from home at the time of the enrollment of the EMM, because I would

not join the loyal EMM. I was a Southern man and did not want to do

it.”

(*) Sidney incorrectly gives the name of “Col. Warren” rather

than the actual name of GEN. WARING, whose troops actually captured him

and who provided paroles for all captured prisoners shortly thereafter

as shown above. The prisoner he refers to, one Peter West, was reported

as “slightly wounded” in the battle of Springfield, Mo. on 8 January

1863 and is not known to have died. Several of Sid’s responses were

designed to obfuscate the truth and provide protection to his fellow

comrades in arms in the Confederate cause. He avoids indicating that he

had any military duty associated with his capture by Waring’s troops, as

well. Probably because he was acting as a spy or, at minimum, a scout

for Shelby. (As an interesting aside here, the officer to whom his

statement was made was none other than Samuel Swinfin Burdett, lawyer,

later Congressman from Missouri, who would become the Commander in Chief

of the Grand Army of the Republic 1885-1886.)

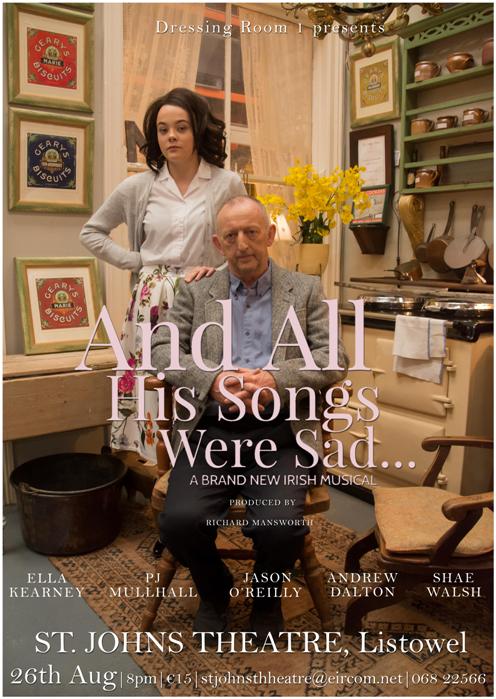

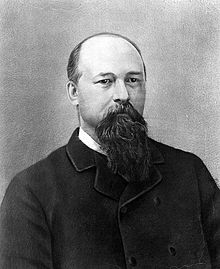

Hon. S. S. Burdett was a member of the First Iowa

Cavalry; served, during the war of the rebellion, as Provost Marshal

General, with headquarters at St. Louis, Mo.; was afterward Member of

Congress for two terms from Missouri; also, was Commissioner of the

General Land Office, which he resigned, and is now practicing his

profession in Washington City.

SOURCE: The History of Clinton County, Iowa: Containing a History of

the County, Its Cities, Towns & Biographical Sketches of Citizens,

January 1, 1879, Western Historical Company, publisher.

Portrait created 1 Jan 1880 by L. Weiser,

National Portrait Gallery

Samuel Swinfin Burdett

|

|

Following his capture in Johnson County, Sid was under

intense scrutiny. His true identity was discovered and depositions taken

to confirm not only his identity, but his allegiance to the “Southern”

cause, and his “disloyalty” which would result in the forfeiture of his

loyalty bond in the amount of $1,500 (a large sum of money in 1863!)

Those deposed to establish his identity were a childhood friend, William

Doniphan, and his father-in-law, Henry Harris Estes. Additionally, one

Robert W. Fleming, a 2d Lieut. in 4th Pro Reg’t with ties to Clay

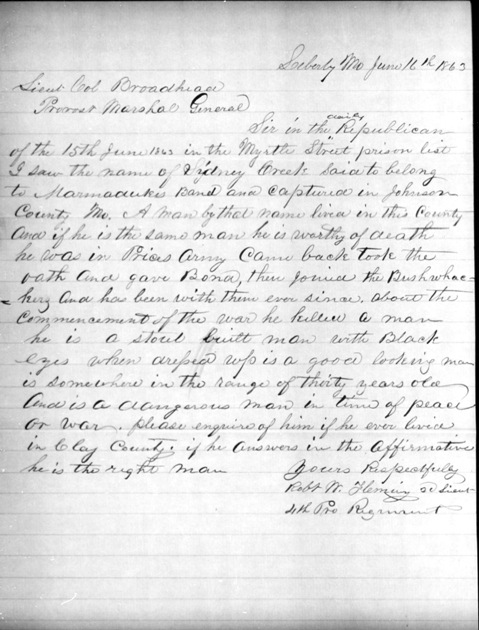

County, Missouri, wrote a venomous letter suggesting Sidney Creek

deserved no less than death as punishment! His claim, undoubtedly,

referred back to the 1860 incident involving the killing of Bernard

Mosby in an altercation with Sid over lumber. No charges were filed; it

being assumed the authorities investigating the matter deemed it a

matter of self-defense. Bernard Mosby was first cousin to John

Singleton Mosby, known more famously as The Gray Ghost during the Civil

War for his daring exploits and flamboyant attire. Given Fleming’s Union

affiliation and unyielding devotion to its cause, it must be assumed

his outrage was vented to Sid as a “bushwhacker” and not related to any

partiality to the Mosby family known for its devotion to the Confederate

cause. Our appreciation for Fleming’s letter lies only in the fact that

he supplies the one description of Sid Creek that exists beyond the

family lore: a “stout man with black eyes” and “when dressed up, is a

good looking man.” No photo of Sid has surfaced but his sister, Virginia

Adolphus Creek, described him as being very tall, a fiercely loyal man,

“a brave and wonderful person,” devoted to the protection of his family

and his homeland.

The other part of Fleming’s letter that may provide

valuable information, if accurate, is that Sid served with Gen. Sterling

“Pap” Price’s Army (actually a state militia) before giving bond in

April of 1862. That would place Sid alongside Old Pap Price’s forces as

they challenged pro-Union forces attempting to oust sitting Governor

Claiborne Jackson. That time frame would have been from April 1861

through about August of 1861 when Price’s troops were forced southward

into Arkansas, leaving Missouri a majority pro-Union state for most of

the War. Fleming states Sid returned and “joined the Bushwhackers.”

Records show he actually enlisted in the C.S.A. in August of 1862, so

any time served alongside his kinfolk with Quantrill’s Raiders would

have been brief, although more than one publication lists his name as

one of Quantrill’s men.

Robert W Fleming Letter of 16 Jun 1863.

After his arrest 31 May 1863, Sid was remanded to

Warrensburg where he was held for some 10 days during which time

evidence was collected to enforce the forfeiture of his bond. By 13 Jun

1863, Sid had been transferred to Gratiot (pronounced “grass-shut”)

Street Military Prison in St. Louis, Missouri, where on the 15th of June

he was examined by S. S. Burdett, Acting Provost Marshal General where

he gave the statement previously referenced. He was held at Gratiot

along with a variety of inmates: citizens who were arrested for

“hallooing for Jefferson Davis” or being drunk or disorderly,

gunrunners, bootleggers who served liquor to slaves, Confederate

prisoners, spies and those suspected of disloyal actions or treasonous

statements. Formerly the McDowell Medical College, Gratiot was a large,

multi-story, rambling building including a dank and dreary basement. Its

transmogrification to a prison was prompted by the over crowding of

nearby Myrtle Street Prison and the impending influx of thousands more

prisoners. The unique mix of inmates made for an unruly situation with

occasional escapes effected without much apparent effort. It was a

miserable place to be although its inmates were spared the horrific

conditions experienced by many in other prison camps such as

Andersonville.

| Absalom Grimes, who spent the majority of 1864 in

these rooms, said, “In those stirring war days no man was of importance

or standing until he had been locked up in Gratiot Street prison at

least a few days… The citizens referred to would be rounded up about

town and locked up without charges, apology, or explanation and after

being boarded for from one week to two months they would be called

before the provost marshal and presented with the oath of allegiance to

the United States, which they had to sign without question, no matter

how great the effort.” |

|

Gratiot Street Military Prison - St. Louis Mo. 1861-1864

It was in this prison Sid would linger while the wheels

of “justice” ground along. On 30 July 1863, the formalities were

dispensed with and the formal Forfeiture of Bond occurred:

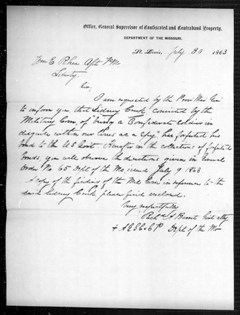

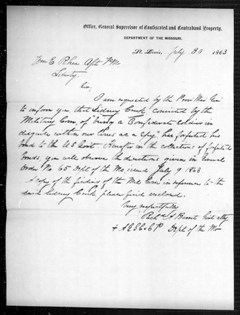

“Sidney Creek, Pvt. – Cpt.

Walton’s Co., Elliott’s Bn. – Clav. Mo. Vol., St. Lewis (sic) “being a

Confederate soldier in disguise within our lines as a spy” has forfeited

his bond to the U.S. Government.

This was soon followed by the

report on 8 August 1863 that “after arrest on the 12th day of April 1862

Sidney Creek gave $1,500 for ‘future loyalty’ and received a parole to

the limits of the said Clay Co.” Things were beginning to wind down.

August 12, 1863, the official action to forfeit the bond was taken by U S

Attorney Richard A. Barrett. This having been accomplished, Sid’s

parole was soon thereafter effected. (SOURCE: "Confiscated and

Contraband Property - Richard A. Barrett, Aug.8, 1863” paper.) |

|

On 26 August 1863, Sidney Washington Creek was paroled

from the Gratiot Street Military Prison. He would once again begin the

arduous trek home from St. Louis to the Northwestern edge of the state.

No more materials have been located which would indicate Sid returned

to action of any kind in the “War of the Rebellion.” All indications

are that he returned to his home, reunited with his wife and family and

undertook the task of rebuilding a life on the farm. He and Lucinda

would add to their family with the birth of Susan Ludicia 25 May 1865,

followed in fairly short order by Lucinda Agnes in 1868, Virginia

Darlisco (known affectionately as Jennie) in 1869, Sarah Lee in 1872

and, finally, little Lillie in 1873.

The final chapter in the life of Sidney Washington

Creek will be published in the September issue of PencilStubs. For many

folks, a simple recitation of the date and cause of death will suffice –

perhaps, even the location where their final remains lie at rest. But

not for our Sid. His was a life filled from start to finish with drama.

That dramatic ending to his life comes next month. Stay tuned.

Click on author's byline for bio and list of other works published by Pencil Stubs Online.