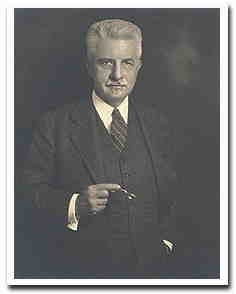

Arthur Lovejoy

Arthur Lovejoy wrote the following: “Whatever other definitions of man be true or false, it is generally admitted that he is distinguished among the creatures by the habit of entertaining general ideas.” Lovejoy was an idea man. Ideas were his stock in trade, specifically ideas about ideas. Intellectual concepts have histories, and this is what fascinated him: how the great ideas developed and mutated and combined and recombined and coursed from century to century. He was an archaeologist of the intellect, digging for the foundations of Western thought, seeking to reduce systems, creeds, and -isms to their fundamental particles. Lovejoy was interested in a rational basis for theology, what he termed “a quest for intelligibility,” so he studied philosophy and comparative religions and applied the techniques of a historian to his intellectual pursuits.

Lovejoy was hired by Stanford in 1899 but quit two years later when the president dismissed a colleague because the latter’s politics had offended a trustee. Harvard’s philosophy department wanted him, but President A. Lawrence Lowell blackballed him as a troublemaker. (Lovejoy would later co-found the American Association of University Professors, perhaps confirming Lowell’s worst fears.)

| Johns Hopkins University, apparently not so easily scared, hired him for its philosophy department in 1910. Lovejoy was a philosophy professor but didn’t like what he considered artificial disciplinary lines. Under him Hopkins became known as the center of historical philosophical thinking. |  |

When Lovejoy looked at ideas, he saw aggregates. He believed that philosophical systems, political creeds, and big ideas about life and God and meaning all could be disassembled into building blocks that he called “unit-ideas.” These units, he said, were passed down and used in new combinations by generation after generation of thinkers. He wrote, “… Most philosophic systems are original or distinctive rather in their patterns than in their components.” That is, past a certain point in history there were no new fundamental ideas, just new ways to combine these unit-ideas. In his most famous book, The Great Chain of Being, he examined the idea, derived by the Neoplatonist philosopher Plotinus from Aristotle and Plato, that all of creation forms a chain. The chain includes all that could possibly exist, starting with God, in an infinite series of forms, each of which shares at least one attribute with its neighbor in the chain. Lovejoy traced this idea through 2,000 years of intellectual history, demonstrating its influence on thought in the West.

An important aspect of Lovejoy’s work was his examination of how the meanings of words changed over time, and the effect those changes had on ideas. He’d take “nature” or “romanticism” and demonstrate how people used these terms without being fully cognizant of the ambiguities caused by shifting definitions. Lovejoy once subjected himself to interrogation by the Maryland Senate, when he’d been nominated for the state’s educational board of regents. A legislator asked Lovejoy if he believed in God. Lovejoy developed at length 33 definitions of the word “God” and asked the committee member which of these meanings he had in mind when putting the question.” As the story goes, no one felt inclined to ask him another question, and Lovejoy was confirmed. Unanimously.

Adapted and condensed by John I. Blair from the article at pages.jh.edu/~jhumag.

No comments:

Post a Comment