Florence Nightingale

On February 7, 1837, she said she heard the voice of God telling her that she had a mission in life. It took her some years of searching to identify that mission. This was the first of four occasions when she claimed God spoke to her.

By 1844, she had chosen a different path than the social life and marriage expected of her by her parents, deciding to work in nursing, then not considered a "proper" profession for women. Florence went to Prussia to experience a German training program for nurses. She worked briefly for a Sisters of Mercy hospital near Paris. Her views began to be respected.

In 1853, Florence became superintendent of London’s Institution for the Care of Sick Gentlewomen. When the Crimean War began, reports came back of terrible conditions for wounded and sick soldiers. Florence volunteered to go to Turkey and, at the urging of a family friend, took 38 women as nurses, including 18 Anglican and Roman Catholic nuns. They accompanied her to the war front, leaving England October 21 and entering the military hospital at Scutari, Turkey, November 5, 1854, where Florence headed nursing efforts in English military hospitals until 1856.

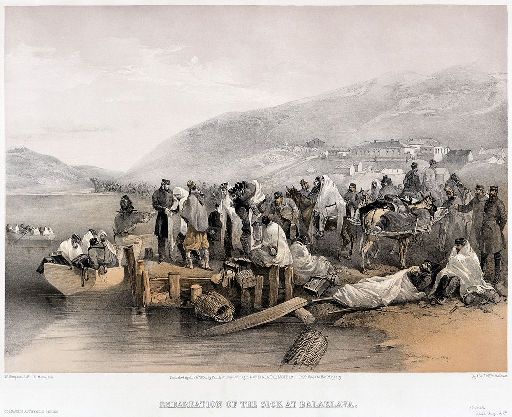

|

Embarkation of Balaklava Soldiers |

She established more-sanitary conditions and ordered supplies, beginning with clothing and bedding. She gradually won over cooperation from the military doctors and used significant funds raised by the London Times. Soon she focused more on administration than on actual nursing, but continued to visit the wards and send letters back home from injured and ill soldiers. Her rule that she be the only woman in the wards at night earned her the title “The Lady with the Lamp.” The mortality rate at the hospital fell from 60% at her arrival to 2% six months later.

| The Lady of the Lamp |  |

Florence Nightingale applied her interest in mathematics to developing statistical analyses of disease and mortality, inventing the use of the pie chart. She fought both a reluctant military bureaucracy and her own illness with Crimean fever to eventually become general superintendent of the Female Nursing Establishment of the Military Hospitals of the Army (March 16, 1856).

Florence was already a heroine in England when she returned, though she actively worked against public adulation. She helped to establish the Royal Commission on the Health of the Army in 1857, giving evidence to the commission and compiling her own report, published privately in 1858. She also became involved – from London – in advising on sanitation in India.

Florence was quite ill from 1857 until the end of her long life, living in London, mostly as an invalid. Her illness, never identified, may have been organic or psychosomatic – some have even suspected it was intentional, to give her privacy and time to continue her writing. In 1860, she founded the Nightingale School and Home for Nurses in London, using funds contributed by the public to honor her work in the Crimea. In 1861, she helped inspire the Liverpool system of district nursing, which later spread widely.

Elizabeth Blackwell’s plan for opening a Woman’s Medical College (it opened in 1868 and continued for 31 years) was developed in consultation with Florence. The King awarded her the Order of Merit in 1907, making Florence Nightingale the first woman to receive that honor. Florence declined the offer of a national funeral and burial at Westminster Abbey, requesting that her grave be marked simply. Only her initials appear on the family marker in a small cemetery in Hampshire.

Drawn from several sources, including:

-

womenshistory.about.com/od/nightingale/p/

-

nightingale.htm

-

geocities.com/~bread_n_roses/nightin.html

-

adelaideinstitute.org/Dissenters1/Muirden/nightingale

1.htm

Click on John I. Blair for bio and list of other works published by Pencil Stubs Online.

No comments:

Post a Comment