A Tragedy That Changed America’s View of Labor Unions

And Other Object Lessons

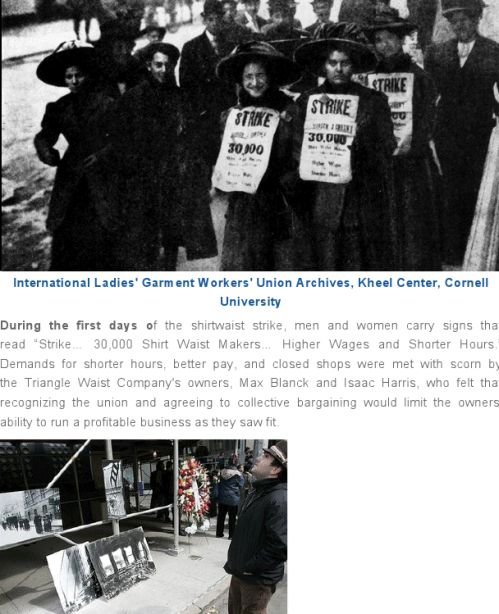

Just a few days past of over a century ago, a massive tragedy of disastrous proportions hit New York City and its garment district. One of the most killing fires burned out the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. So why bring it up now? Because we have a new bunch of bastardly bad asses who think Unions are destroying the world they love to live in – the world of slave labor and billionaires Let’s bring this story up again just so we understand the ilk who are now advocating new laws designed to deter labor unions and working people in general. Did we really want to put into office all those Repugs and Tea Party morons who will put America back to the 19th century? Somehow I would like to think that we were carried away in our efforts to wake up the Washington war lords. Well, whatever, here is the story as I researched it. And, yes, it is Pro Union, just like me.

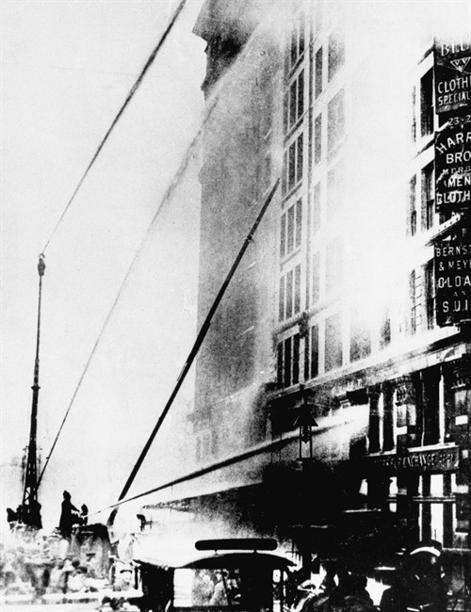

On Saturday, March 25, 1911, minutes before more than 600 workers were to leave for the evening, a small fire began on the eighth floor of the Triangle factory. The flames reached bundles of material that hung from the tall workroom ceilings and then swept along a carpet of highly combustible lawn scraps that had accumulated on the wooden floor for two months. Flames quickly spread through open windows to the top two floors, and within minutes the fire consumed the entire loft factory.

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, variously known, as it swept through Congress, as the Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act of 2002, Corporate and Auditing Accountability, Responsibility, and Transparency Act of 2002, Corporate Responsibility Act, the Corporate Fraud and Accountability Act, Justice for Victims of Corporate Fraud Act, the Corporate and Criminal Fraud Accountability Act, the Public Company Accountability Act, and just generally as "What on earth were you people thinking when you decided to engage in this kind of financial reporting and analysis? Act." Sarbanes-Oxley marks the third great regulatory reform for publicly held companies. First, there were the new laws and reforms on insider trading and junk bonds following the Ivan Boesky and Michael Milken debacles. Then there were the reforms that came about as a result of the collapse of savings and loans. "Never again," those responsible for these reforms and legislation muttered. With new requirements, new sanctions, new penalties, new public disgrace, no one would ever be so bold as to perpetrate schemes and artifices on the market ever again. Yet, here we are again. And we are tackling the same sort of task: How do we prevent corporations from trotting down these temporarily lucrative paths of fraud? What types of checks and balances could we create that would prevent such frauds?

The Triangle Shirtwaist fire was the deadliest workplace accident in New York City’s history. After the fire, the women workers’ stories inspired hundreds of activists across the state and the nation to push for fundamental reforms. For some, such as Frances Perkins, who stood helpless watching the factory burn, the tragedy inspired a lifetime of advocacy for workers’ rights. She later became secretary of labor under President Franklin Roosevelt.

March 25th marked the 100th anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, New York's landmark industrial disaster that killed 146 of the factory's employees — most of them young immigrant women and girls of Italian and European Jewish descent. The tragedy sparked nationwide debate on workers' rights, representation and safety.

An officer stands at the Asch Building's 9th floor window after the Triangle fire. Sewing machine wreckage of the Triangle factory fire are piled in the center of the blaze damaged area.

|

Working people around the country are commemorating the 100th anniversary of the tragic Triangle Shirtwaist fire, which killed 146 workers, mostly young immigrant women, many of whom jumped to their deaths from the 10-story factory to escape the fire because they were locked inside.

FILE - In this March 25, 1911 file photo, firefighters work to put out the fire.

NEW YORK, N.Y. - It was a warm spring Saturday when dozens of immigrant girls and women leapt to their deaths — some with their clothes on fire, some holding hands — as horrified onlookers watched the Triangle Shirtwaist factory burn.

The March 25, 1911, fire that killed 146 workers became a touchstone for the organized labor movement, spurred laws that required fire drills and shed light on the lives of young immigrant workers near the turn of the century.

The 100th anniversary comes as public workers in Wisconsin, Ohio and elsewhere protest efforts to limit collective bargaining rights in response to state budget woes. Labor leaders and others say one need only look to the Triangle fire to see why unions are crucial.

"This is a story that needs to be told and retold," said Cecilia Rubino, the writer-director of "From the Fire," an oratorio inspired by the Triangle fire. "We don't have that many moments in our history where you see so clearly the gears of history shift."

To mark the centennial, hundreds of theatrical performances, museum exhibits, lectures, poetry readings, rallies and panel discussions are taking place nationwide. Two documentaries have aired on TV; PBS' "Triangle Fire" premiered Feb. 28 and HBO's "Triangle: Remembering the Fire" on Monday.

Descendants of victims and survivors of the fire will gather Friday for a procession to the site in Manhattan's Greenwich Village. The building now houses New York University classrooms and labs.

Suzanne Pred Bass, a Manhattan psychotherapist and theatre producer, is the great-niece of Katie Weiner, who survived the Triangle fire, and of Rose Weiner, who did not.

Bass ticked off the reasons why people remain fascinated by the Triangle fire after 100 years.

"It's the youth of these women," she said. "It's the tragedy, it's the changes it spawned and it's the immigrant experience."

The fire started at end of the workday and raced from the eighth floor to the ninth and 10th. As hundreds of workers — mainly Jewish and Italian immigrant women and girls, the youngest 14 — tried to escape, they found a crucial door apparently locked so that workers were locked in at their work until the owners decided that it was the end of the workday

"They were panic-stricken," said Eileen Nevitt, whose grandmother Annie Sprinsock survived. "It was hellacious, and they ran for their lives the best they could."

Firefighters rushed to the scene and raised their ladders, which reached only to the sixth floor. The fire was under control in 18 minutes — too late.

At the trial later that year of Triangle owners Max Blanck and Isaac Harris on manslaughter charges, survivors testified that their escape had been blocked by a locked door on the ninth floor. Some said the door was kept locked to prevent theft.

Katie Weiner said she felt for the door, which she could not see in the smoke, and turned the knob.

"I pushed it toward myself and I couldn't open it and then I pushed it inward and it wouldn't go and I then cried out, 'The door is locked!'" she testified.

Meanwhile, the elevator shuttled up and down carrying as many workers as could cram into it. Weiner joined the crush for the last elevator but was pushed back. She testified that she grabbed the elevator cable and threw herself in, landing on girls' heads. She was the last person out of the burning building.

The jury heard from 155 witnesses before returning a verdict of not guilty.

"I believed that the door was locked at the time of the fire," one juror said. "But we couldn't find them guilty unless we believed they knew the door was locked."

Workers' advocates continued to blame Blanck and Harris, who had resisted a union drive in 1909.

Blanck's granddaughter Susan Harris said she is saddened when people demonize her grandfather, who died before she was born

"It's really important for them, I think, to have a villain," she said.

Blanck and Harris were on the 10th floor when the fire started and were able to escape to the roof. But several of Susan Harris' relatives died in the fire, including Jacob, Essie and Morris Bernstein, members of Blanck's wife's family who worked at Triangle.

Harris lives in Los Angeles but is spending March in New York to take part in Triangle commemorations. An artwork she created to honour the fire victims — made of antique shirtwaists and handkerchiefs — will be displayed at the New York City Fire Museum for a month.

One witness to the Triangle workers' death plunges was Frances Perkins, who later became the first female Cabinet member when President Franklin Roosevelt appointed her secretary of labour. Perkins was having tea nearby and heard the commotion. She ran to the scene as the first body hit the ground.

"That fire is the event that changed her life and that really changed the course of American history," said Kirsten Downey, author of a book about Perkins, "The Woman behind the New Deal."

Perkins was appointed to the Factory Investigating Commission, convened in response to the Triangle fire, and the panel held hearings all over New York state before drafting 20 laws aimed at improving workplace safety. Some of the new laws required fire drills, set occupancy limits in buildings and required exit signs to be clearly posted.

"Policies that were enacted because of that fire permeate American workplaces now," Downey said.

Days after the Triangle fire, 100,000 mourners marched in a funeral procession through the streets of New York, while another 250,000 lined the route. Their grief built support for the right of garment workers to unionize.

"It created a strong garment workers union," said Bruce Raynor, president of Workers United, the 21st-century heir to the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. "It helped to really start the modern labour movement."

He said the Triangle fire commemoration resonates strongly today, given the labour struggles across the country and in Wisconsin, where a law passed this month limits public workers' collective bargaining rights.

"One hundred years later, 150,000 people are protesting in Madison, Wis., over the same issue," he said: "the right of working people to organize."

It was a warm spring Saturday when dozens of immigrant girls and women leapt to their deaths -- some with their clothes on fire, some holding hands -- as horrified onlookers watched the Triangle Shirtwaist factory burn.

The March 25, 1911, fire that killed 146 workers became a touchstone for the organized labor movement, spurred laws that required fire drills and shed light on the lives of young immigrant workers near the turn of the century.

The 100th anniversary comes as public workers in Wisconsin, Ohio and elsewhere protest efforts to limit collective bargaining rights in response to state budget woes. Labor leaders and others say one need only look to the Triangle fire to see why unions are crucial.

"This is a story that needs to be told and retold," said Cecilia Rubino, the writer-director of "From the Fire," an oratorio inspired by the Triangle fire. "We don't have that many moments in our history where you see so clearly the gears of history shift."

To mark the centennial, hundreds of theatrical performances, museum exhibits, lectures, poetry readings, rallies and panel discussions are taking place nationwide. Two documentaries have aired on TV; PBS' "Triangle Fire" premiered Feb. 28 and HBO's "Triangle: Remembering the Fire" on Monday.

Events: Descendants of victims and survivors of the fire will gather Friday for a procession to the site in Manhattan's Greenwich Village. The building now houses New York University classrooms and labs.

Suzanne Pred Bass, a Manhattan psychotherapist and theater producer, is the great-niece of Katie Weiner, who survived the Triangle fire, and of Rose Weiner, who did not.

Bass ticked off the reasons why people remain fascinated by the Triangle fire after 100 years.

"It's the youth of these women," she said. "It's the tragedy, it's the changes it spawned and it's the immigrant experience."

The fire started at end of the workday and raced from the eighth floor to the ninth and 10th. As hundreds of workers -- mainly Jewish and Italian immigrant women and girls, the youngest 14 -- tried to escape, they found a crucial door apparently locked.

"They were panic-stricken," said Eileen Nevitt, whose grandmother Annie Sprinsock survived. "It was hellacious, and they ran for their lives the best they could."

Firefighters rushed to the scene and raised their ladders, which reached only to the sixth floor. The fire was under control in 18 minutes -- too late.

Trial: At the trial later that year of Triangle owners Max Blanck and Isaac Harris on manslaughter charges, survivors testified that their escape had been blocked by a locked door on the ninth floor. Some said the door was kept locked to prevent theft.

Katie Weiner said she felt for the door, which she could not see in the smoke, and turned the knob.

"I pushed it toward myself and I couldn't open it and then I pushed it inward and it wouldn't go and I then cried out, 'The door is locked!'" she testified.

Meanwhile, the elevator shuttled up and down carrying as many workers as could cram into it. Weiner joined the crush for the last elevator but was pushed back. She testified that she grabbed the elevator cable and threw herself in, landing on girls' heads. She was the last person out of the burning building.

The jury heard from 155 witnesses before returning a verdict of not guilty.

"I believed that the door was locked at the time of the fire," one juror said. "But we couldn't find them guilty unless we believed they knew the door was locked."

Workers' advocates continued to blame Blanck and Harris, who had resisted a union drive in 1909.

Blanck's granddaughter Susan Harris said she is saddened when people demonize her grandfather, who died before she was born

"It's really important for them, I think, to have a villain," she said.

Blanck and Harris were on the 10th floor when the fire started and were able to escape to the roof. But several of Susan Harris' relatives died in the fire, including Jacob, Essie and Morris Bernstein, members of Blanck's wife's family who worked at Triangle.

Harris lives in Los Angeles but is spending March in New York to take part in Triangle commemorations. An artwork she created to honor the fire victims -- made of antique shirtwaists and handkerchiefs -- will be displayed at the New York City Fire Museum for a month.

Changes: One witness to the Triangle workers' death plunges was Frances Perkins, who later became the first female Cabinet member when President Franklin Roosevelt appointed her secretary of labor. Perkins was having tea nearby and heard the commotion. She ran to the scene as the first body hit the ground.

"That fire is the event that changed her life and that really changed the course of American history," said Kirsten Downey, author of a book about Perkins, "The Woman Behind the New Deal."

Perkins was appointed to the Factory Investigating Commission, convened in response to the Triangle fire, and the panel held hearings all over New York state before drafting 20 laws aimed at improving workplace safety. Some of the new laws required fire drills, set occupancy limits in buildings and required exit signs to be clearly posted.

"Policies that were enacted because of that fire permeate American workplaces now," Downey said.

Days after the Triangle fire, 100,000 mourners marched in a funeral procession through the streets of New York, while another 250,000 lined the route. Their grief built support for the right of garment workers to unionize.

"It created a strong garment workers union," said Bruce Raynor, president of Workers United, the 21st-century heir to the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. "It helped to really start the modern labor movement."

He said the Triangle fire commemoration resonates strongly today, given the labor struggles across the country and in Wisconsin, where a law passed this month limits public workers' collective bargaining rights.

"One hundred years later, 150,000 people are protesting in Madison, Wis., over the same issue," he said: "the right of working people to organize."

Researched by: Leo C. Helmer, for Pencilstubs. March 2011