Puff, Puff . .

Puff, Puff . .

And better friends I’ll not be knowing;

Yet there isn’t a train I wouldn’t take,

No matter where it’s going.

(Edna St. Vincent Millay.)

Because I have been employed by a bus company for more than three and a half decades I have force fed you with bus lore. I have paid little or no attention to trains. Yet trains and railways have been part of our culture since the first half of the nineteenth century.

| Since the first railway was built in Ireland from Dublin to Kingstown (now Dun Laoighre) our trains have been lauded (and criticised) in song and story. |

You had the famous ballad The Oul Buncrana Train and The West Clare Railway immortalised by Percy French. In Ireland’s struggle for independence the railways featured prominently: Dan Breen an his comrades would ensure that “The Station of Knocklong” would go down in history.

When the last train left Listowel Sean McCarthy wrote a ballad about it titled, The Abandoned Railway. In a later radio interview he recounted his train journeys as a child,

“The more knowing passengers put their backs to the engine. Of course the younger passengers wanted to see everything, because it’s easier to see out from the back seat of a carriage... when it gets up steam you know who the cute ones were. Because the smoke blew in through the window. And especially if there was new gravel or anything . . . in through the window. You could make your own rhyme out of the wheels. You could make anything up out of the ‘chug, chug’of the wheels.”

In the early 1960s the future of the railways did not seem to be particularly threatened. The swingeing closures of 1956/7 on the former GNR seemed to have consolidated the network, and it appeared that steam traction would only gradually disappear. The Benson Report was commissioned in Northern Ireland in 1963, a little after the McKinsey Report in the Republic.

The major part of both these reports was implemented resulting in a further set of closures - in the south the West Cork lines, the bulk of the DSER inland routes and many minor branches fell to the axe, while in the north the GNR "Derry Road" finally succumbed. However, it looked as though the railways would escape any further closures, and the investments in new locomotives, railcars and coaches seemed to suggest that the future for the surviving lines was secure.

85 at Dundalk. Photo by Barry Carse. |  |

It was in such a climate that the following events unfolded. Shortly after a railtour to Portrush, organised by the Inst (Royal Belfast Academical Institution) Railway Society in September 1963, an ad hoc organisation was set up to run steam railtours in the last days of steam. This was known as the "Northern Ireland Railway Societies Joint Committee", and was empowered by the committees of the Irish Railway Record Society (Belfast Area), the Royal Belfast Academical Institution (Inst) Railway Society, the Northern Ireland Road and Rail Development Association, and the Friends of the Belfast Transport Museum to organise and run railtours on their behalf, as none of these societies felt that they had enough financial resources or a large enough membership base to do so on their own.

Derek Young (NIRRDA), Michael Shannon (FBTM), Denis Grimshaw (as secretary), Sullivan Boomer (RBAIRS), John McGuigan (IRRS) and Craig Robb were the members of the NIRSJC. Incidentally, the NIRSJC had absolutely no constitution, official or legal status whatsoever - but people didn't worry about things like that in those days! A successful railtour was operated from Belfast to Loughrea and back on 4th April 1964, with VS No.207 from Belfast to Dublin and back, although the Dublin - Loughrea section was operated by a diesel railcar set instead of steam traction as originally intended - not because CIÉ would not agree to steam, but purely on grounds of cost.

The major factor which had killed off the idea of using one or two of CIÉ's remaining J15s (or GNRI Qs No.131 or No.132, at least one of which was considered to be repairable) from Dublin to Loughrea and back was CIÉ's estimated locomotive repair costs. The only market for railtours in the 1960s was considered to be the railway enthusiast market - no Portrush Flyers, Santa Trains or other general public ventures were considered viable - really because the general public still thought of steam trains as normal everyday transport. The virtual end of steam operations on CIÉ, and the apparently rapidly approaching demise of steam on the UTA (before the Magheramorne Spoil Contract deferred the evil day!), together with the experience of the Loughrea tour were instrumental in turning the thoughts of three of the Joint Committee's members to establishing a preservation society which would own the locomotives, keep them in traffic, and could overhaul and maintain them largely with volunteer labour.

The examples of the Bluebell and Keithley & Worth Valley Railways in Britain were noted, but widespread main line operations were always considered vital, rather than an attempt to purchase and operate a branch line or other section of closed railway. The other fundamental decision, based on market potential for railtour passengers, availability of representative locomotives and rolling-stock from all former Irish railways and a larger variety of routes for special trains, together with the potential for a larger membership base, and not from any political considerations, was to establish the new society on an all-Ireland basis. Even the very limited experience of the Loughrea tour had indicated that better access to the potential railtour market in the Dublin area could have helped the venture.

So it was that following the Loughrea railtour in April 1964 Derek Young, Michael Shannon and Denis Grimshaw met in York Road waiting room (quite a spacious and comfortable place in those days) on several occasions. And it was there, in the early summer of 1964, that the decision to set up the RPSI (and the choice of name) was made.

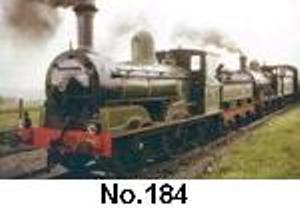

That dedicated group of enthusiasts decided to take some action to preserve our railway heritage. In September 1964 the Railway Preservation Society of Ireland was formed. They rescued steam locomotives and coaches and now they have an impressive collection of working steam trains. They run an annual steam train programme as well as hiring trains for parties and corporate outings.

Their trains have been used in such films as The First Great Train Robbery, Angela’a Ashes, Michael Collins, The Irish RM, Lassie, The Wind That Shakes the Barley and many more.

The engineering branch is in Whitehead County Antrim and some of the maintenance work is carried out at Mullingar and Inchicore.

| Blackshade. Photo by Barry Carse. |

Thanks to the foresight of that small band of men in 1964 it is still possible to take a nostalgic trip on a steam train in Ireland.

The Railway Preservation of Ireland can be contacted at:

Docklands Innovation Park

128-130 East Wall Road, Dublin 3.

Their website is: steamtrainsireland.com

No comments:

Post a Comment