Always Looking – The Story of Liberal, Missouri

Not so long ago I wrote a column about the role of religion in the settlement of America, about its central place in much of our history and society. Most American towns have had churches at, or near, their centers.

But not every town.

Liberal, Missouri, is a quiet – almost somnolent – small town in western Barton County. Quiet people – many of them retired – quiet streets. You’d never in a million years think of this as a hotbed of radicalism. Unless you notice there is a street named after Charles Darwin, author of the Theory of Evolution; another named for Robert G. Ingersoll, 19-century freethinker, humanist, and brilliant orator; and a third evidently named for Peter Payne, 15th-century Lollard heretic (follower of John Wyclif), later a Taborite (part of the Hussite movement in Bohemia).

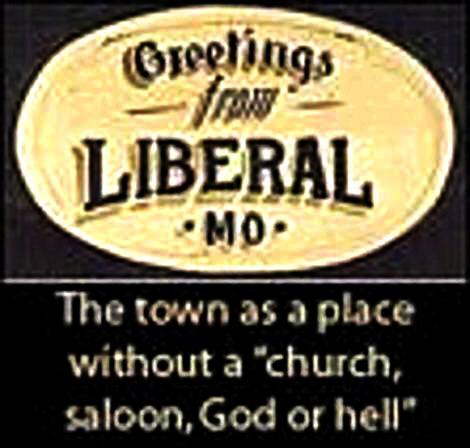

In fact, at its inception, Liberal was an extraordinary social experiment, unique (so far as I know) in America. Instead of being founded as a city of churches, it was founded, deliberately, to be a city without churches – a Utopian city of Freethinkers.

George H. Walser (after whom another Liberal street is named) was a poetry-writing attorney from Indiana. Following Civil War service, he moved to Barton County and set up what soon became a very successful law practice. Having already been a member of a local Freethinkers group in the county seat, Lamar, but finding his beliefs too unpopular there, in 1880 he bought 2,000 acres of prime farmland 17 miles northwest of Lamar and planned an experiment in intellectual community living, along the lines of the New Harmony, Indiana, community of a generation earlier. He wanted a place where atheists could come and live in a churchless – and saloonless – town where people could raise their children without religion, a place where freethinkers could live to their standards of decency and morality in a quiet, unmolested way, away from missionaries and the barrage of religion. Christians were not to be allowed. Liberal was advertised as “the only town of its size in the United States without a priest, preacher, church, saloon, God, Jesus, hell or devil.”

|

In harmony with the purpose for organizing the town, a number of unusual institutions, designed to promote the ideal community, were tried in Liberal during the 1880s and 1890s. The first of these was a Sunday Morning Instruction School, where children were taught from “Youth Liberal Guide” and from various works on physics, chemistry, and other sciences. In another class organized for older young people, elementary experiments in the physical sciences were performed under the supervision of teachers whose avowed function was to encourage and direct free, intelligent discussions. An orphanage was begun where Free Thought was the rule. In a structure called the Universal Mental Liberty Hall, lectures were given each Sunday evening, and scientists, philosophers, socialists, atheists, Protestant ministers and Catholic priests were invited to speak – respectable decorum being the only limitation placed upon any speaker. Large, enthusiastic crowds gathered there each week in the interest of mental liberty. The Liberal Normal School and Business Institute was another institution organized by Walser to promote liberal education free from the bias of Christian theology. This school was well-advertised and soon had a large enrollment. According to a tract published in 1885, the Liberal Normal School and Business Institute was “located in the liberal town, taught by liberal teachers and courted only the patronage of liberal patrons.” Out of this organization developed Free Thought University, which opened in 1886 with a staff of seven teachers and a course of study “untrammeled by Bible, creed, or isms.”

|

Free Thought University |

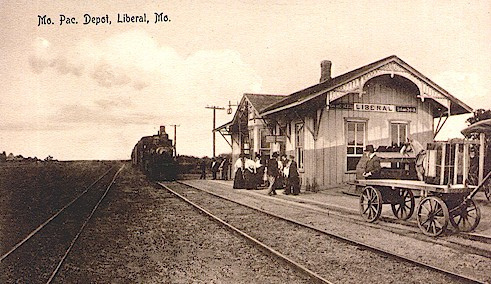

There were actually people at the train station warning Christians that they were not welcome. So naturally some Christians barraged the town on missions to convert the heathens.

|

In spite of the fence, and the warnings, more Christians came, bought homes, and quietly began holding religious services, although Walser more than once managed to put a stop to the services by proving he still had part ownership of property where they were being held, hence the right to control activity there. The services were moved to Pedro. (There still is a street in west Liberal named Pedro.)

People throughout the county, the state, and even other parts of the country, took interest and took sides – mostly the side of the Christians. Unfavorable, and perhaps libelous, articles, pamphlets, and books were written and published. Accusations of rampant drunkenness, divorce, loose morals, and even open practice of birth control, were made. For example, “In no town is slander more prevalent, or the charges more vile. If one were to accept what the inhabitants say of each other, he would conclude that there is a hell, including all Liberal, and that its inhabitants are the devils.” [St. Louis Post-Dispatch 1885, in an Op-Ed piece quoting an anti-Liberal pamphlet]

Inevitably, with all the controversy, passionate opposition, and bad publicity, the town’s real estate values and commercial activity suffered and many of the settlers lost their investment. Ultimately both churches and saloons did move in. The Universal Mental Liberty Hall was sold to the Methodists. Walser was converted, first to Spiritualism, eventually, before his death in 1910, to Christianity. The experiment had failed. Only the street names, a few recycled buildings, and some unusual memories were left. Oh, and the cemetery specially designed by Walser in which all the markers are arranged in concentric rings around a central circular space where Walser himself was to have been buried, supposedly to be the first thing resurrected people would see when they arose from the grave. (He was actually buried in Lamar.) Nowadays there are seven churches in Liberal, one for every 100 citizens.

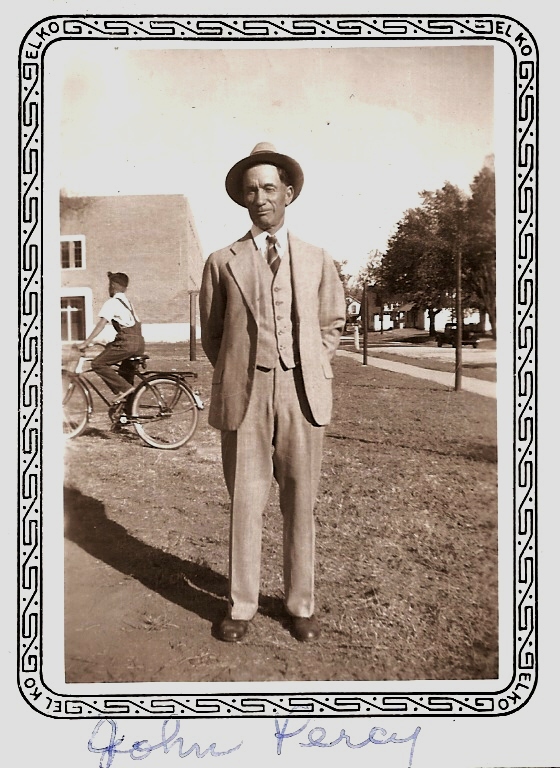

And why do I take interest in this obscure, somewhat bizarre, bit of American history? Liberal, Missouri, is the town where, when I was a boy growing up in the 1940s and 1950s, once or twice a year I traveled with my family to visit my one and only living grandparent, Grandpa Percy. If I gave any thought at all to the character of his hometown, it was to judge it as a conservative backwater where the town generator was turned off at 10:00 p.m. (and we went to bed by kerosene lamps), sidewalks were rumpled expanses of locally molded and fired red bricks stamped “Liberal” (I have a few of these in my garden walk here in Texas), half the shops on the two-block main street were closed and the others looked ready to close, and the closest approach to higher education was the old public school building down the street from Grandpa’s house where to me the main attraction was a big steel merry-go-round and an unusually high, hump-backed, slide on the playground. (See pic of Grandpa Ernest John Percy on the school grounds at bottom of Page.)

The moral to this story is (at least) threefold: (1) the story of America is richly textured, (2) even the sleepiest little backwater can hide a history you would never guess at, and (3) don’t try to start a radical social experiment in the heart of the Bible Belt and expect it to thrive.

© 2010 John I. Blair [with materials drawn from an article at Ziztur.com, the article on Liberal in Wikipedia, and personal observation; there is a surprising amount of information on the Internet about Liberal for an obscure country town of 700 population]

Click on

John I. Blair

for bio and list of other works published by Pencil Stubs Online.

No comments:

Post a Comment