Always Looking; How We Re-made the Face of America, and Why

During my wanderings around books and Websites and libraries in search of family history, many things have struck me. (My wife may think a 2x4 should have been one of them.) Among these is this very obvious observation: America no longer looks much like we found it.

Most places in North America, except for those too remote for settlement, or those very carefully preserved (or restored) to save a bit of the past, would be unrecognizable to the first people who came here from other countries, much less to the Native Americans who lived here for thousands of years before outsiders “discovered” the place. Insofar as we were capable, we have totally rebuilt the place, at incalculable cost in labor, time, and money, and in many cases incalculable cost to the landscape and ecology and our own wellbeing.

Some of this is pretty obvious – New York City, with its miles of solidly built blocks of towering masonry and steel over level after level of subway, railway, and auto tunnels, sewers and aqueducts, has obliterated the rocky, boggy place that was Manhattan Island in the 1600s. Not even Central Park is like the original landscape – it’s a carefully constructed landscape incorporating existing rock formations into a new surface of artificial meadows and woodlands and lakes, roads and paths and gardens.

Perhaps not so obvious, though no less radical, is the change in the typical countryside scene. When Europeans first came to the New World, they found thousands of square miles of primeval forest, swamp, prairie. Now, in most states outside the West, the forest has been leveled, swamps drained, prairies plowed. Typical across most of the eastern and middle parts of the country, plus the fertile valleys of the West Coast, are tended fields, regularly harvested woodlots, managed pastures dotted with hundreds of thousands of artificial ponds for watering livestock. End result: scenes in central Ohio – once a wild, virtually trackless forest – now look not that different from scenes in central Iowa – once a treeless tallgrass prairie. Straight section line roads, clean fields, fences. All the “wild” quite obliterated. And the why? To make the land productive and profitable as farms. Settlers in Ohio and similar areas spent generations cutting down trees and pulling stumps; in Iowa and Kansas and similar areas, they spent generations busting sod, planting trees where needed, building ponds. In Louisiana or Mississippi or Florida – generations draining swamps (and cutting down trees).

Modern generations have an almost impossible time even imagining what the land looked like before. There are no photographs of most of it (although some remain of the virgin prairies, or of the vast forests of the old Northwest Territories of Michigan and Wisconsin and Minnesota).

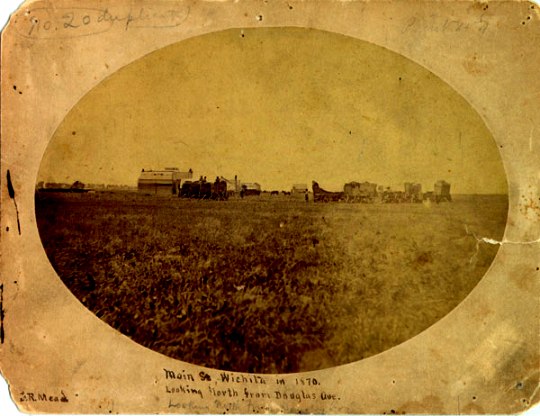

I look, for example, at a rare old photo [photo 1 here] of my hometown, Wichita, Kansas, in about 1870.

|

A double row of tents and crude shacks along a wide and muddy “street”, all surrounded by prairie grass and sunflowers. Then a photo of central Wichita today [photo 2 here] –

block after block of concrete, brick, glass and steel, much like any other American city of the 21st century.

Not a shred of the original prairie remains in that part of Wichita, or in any part of Wichita I can recall.

Or I look at side-by-side photos of virgin tallgrass prairie and an irrigated field of soybeans in Kansas. [photos 3 and 4]

|

Who would guess, looking at the field, that it once also was covered by tall grasses and flowers, growing from sod a foot thick? (The virgin grassland in the first photo, in northern Kansas, has survived because it grows over shallow rock that prevents plowing.)

And like most of us, my ancestors had a great deal to do with this radical transformation of the land. They were proud of turning wilderness into civilization, forest into farms, prairie into plowed fields. We take our present landscape for granted, in large part, because of the incredible amount of work – blood, sweat, and tears – our ancestors expended to make it.

But we also tend to ignore what this change in the land has cost us. Clean air and clean water have been at risk for generations. Myriads of wildlife have vanished, including hundreds of entire species. Many of the natural resources in timber, minerals, food have been severely depleted. Most of us live in crowded circumstances, far different from the spacious “elbow-room” people like Daniel Boone reveled in (and helped to destroy).

So what can we do? Just like we “can’t give it back to the Indians”, we can’t turn it back into wilderness. Too late for that, not while all 300 million plus of us are living here. But we can, individually and in groups, work to improve what we’ve got left. Support the National Parks system and local park systems. Plant trees. Practice greenscaping. Encourage builders who try to preserve or restore natural vegetation. Join conservation groups. (For example, here in Arlington, Texas, my wife and I are members of the Arlington Conservation Council (http://www.arlingtonconservationcouncil.org/) and we try to stay active in national groups such as Sierra Club, Environmental Defense Fund, National Wildlife Federation, World Wildlife Federation, and the Nature Conservancy. Recycle. Walk or bike when you can. Each of these may seem, in itself, tiny and futile; but collectively, they make a difference.)

Perhaps the heroic, gargantuan tasks our ancestors accomplished to make a home for themselves and their descendants may not have been well-thought-out; but in the end they just meant for us, the children of their future, to be safe and happy. Let’s not disappoint them; instead, let’s improve on their vision by correcting some of the more destructive consequences of past roads to settling the continent. ©2010 John I. Blair

No comments:

Post a Comment