I would like to share with you another somewhat parallel, but very different, story from American history, one with a special importance to me because of a connection to my own family’s history. And one, I believe, that illustrates the possible results of following some basic principles of how we humans should live our lives.

In 1774 a girl named Frances Slocum was born in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, daughter of a Quaker family who had lived there since being driven from Massachusetts Bay Colony by persecution for their faith. Drawn by the promise of rich, newly opened land in the Wyoming Valley of the Susquehanna River, near present-day Wilkes-Barre, in 1777 the Slocum family moved to what was then dangerous frontier wilderness, land that, as they soon learned, was in bitter dispute, claimed by both Connecticut and Pennsylvania, and also by the powerful Iroquois Confederation of Native Americans whose villages were located near the headwaters of the Susquehanna.

Even as the Slocum family was relocating, the colonies were in open rebellion from England. Battles had already been fought. And the frontier was not a safe haven from this conflict. The Iroquois and their allies had aligned themselves with the British. The colonists in the Wyoming Valley proceeded to build a series of small forts for shelter and mustered a ragged militia of untrained farmers, old men, boys, and rejects from George Washington’s army, “the undisciplined, the youthful and the aged” as they were later memorialized. A great-great-great uncle of mine was a “captain” in that militia.

In July 1778 attack came. A combined force of British troops, Iroquois, Delaware and other Indians moved down from the north to just above Wyoming. The settlers’ force marched out to attack, but were tricked into an ambush that left many of them dead and the rest in a disordered retreat. Before the fighting and its bloody aftermath were over, many more settlers, including noncombatants, were killed, and the rest were in panicked flight from the Valley.

One family that remained, however, were the Slocums. Frances’ father, being a Quaker, had refused to participate in the fighting and trusted to his peaceful and friendly behavior to protect them from harm. Unfortunately, not all the Indians recognized this trust, especially as one of the Slocum boys was known to have participated in the fight. Later that autumn, in early November, the Slocum farm was raided by a small band of Delaware. A boy staying with the Slocums was killed and Frances, found hiding under a staircase, was taken captive.

Only a month later, in a separate incident, Frances’ father and grandfather were killed as they worked a field. Frances’ surviving family fled for awhile, but returned to their farm when it became possible. And they never forgot her. As soon as they could, her brothers searched for her, but without success. Not until 59 years later did her family finally locate her and learn what had happened to her. And that’s where the rest of the story begins.

As I said, Frances’ story is well-known in American history. Her loss, the decades-long search, and eventual rediscovery, became a part of American folklore. She became “The Lost Sister of Wyoming.” Monuments exist to her memory. Poems were written. Parks and schools have been named for her. Her tale became mythic. But she was a very real person, who lived a long, productive life and made some strong decisions during that life. As I said, my family history touches hers. Not only did the family of my great-great grandmother, Catharine Marvin Baker Reeves, live briefly in the Wyoming Valley during the Revolution, Catharine herself lived for several years just across a small Indiana river, the Mississinewa, from the elderly Frances and may have known her personally. I like to think so.

But what was Frances’ story, and how was she “found” 59 years after disappearing into the wild forests of Pennsylvania, slung over the shoulder of a Delaware Indian, her auburn hair hanging down his back as her mother saw her tear-streaked face for the last time?

After her abduction, Frances was carried miles away, hidden overnight in a cave, then taken many more miles, ultimately as far as the Niagara River area. She was adopted into a Delaware family to be raised as their own daughter, replacing a daughter who had died. She was given the Delaware name We-Let-A-Wash. Her adoptive father, Tuck Horse, who spoke English well from contact with the British, interestingly also made chairs and played the violin skillfully enough to be asked occasionally to play for the local English. Her adoptive mother made and sold brooms and baskets.

During the unsettled times following the end of the Revolution, her new family moved farther and farther away from the eastern colonies, now states in the new country, eventually settling near what is now Fort Wayne, Indiana. Frances was taught a myriad of skills appropriate to her new life – how to cure and sew skins, how to hunt and fish, how to ride a horse, how to live a nomadic life. And she was brought also into the spiritual life of her new people. She became a Delaware in every respect but her skin and hair color and remaining memories of her early childhood.

During her mother’s lifetime the search for Frances was never abandoned. Several times her brothers, and once even her mother, traveled hundreds of miles by horseback through the wilderness, following up on stories and rumors, offering rewards for her return, with no success. Her mother died at age 71 in 1807, still hoping for her Frances to be found.

Years passed. Of her nine brothers and sisters, only four were still living. Then, in 1835, a trader traveling through the Miami Nation country along the Wabash in Indiana was forced to stop for the night at a Miami house. The people there generously gave him shelter and food, as was their custom. He noticed that the eldest of the family, a woman in her 60s who was treated with great honor by the others, had unusually fine-textured, fair hair and pale skin, even white where it was protected from the sun. After the rest of the family had retired for the night, the old lady stayed, asked him to listen and, reluctantly and with much trepidation, told him that she had been taken as a girl from her home on the Susquehanna and raised among the Indians, so long ago that she no longer remembered how to speak English. (He was fluent in Miami.) She remembered her family name, Slocum, and that her family had been Quakers, but not her given name. She had never told anyone before, as she did not want to be taken from her children, grandchildren and friends and the life that she had known for so long; but at this time in her life she was very ill and thought she was dying, so she felt the truth finally should be told or she “would have no rest in the Spirit World.”

On returning home the trader told his mother, who urged him to send a letter to Pennsylvania, advising of his discovery. He did, but through neglect it was another two years before the letter was made public, in a newspaper that found its way into the hands of a friend of the Slocum family. As soon as possible, three very excited members of the Slocum family arranged to travel to visit Frances at her home near Peru, Indiana. They were able to identify her without doubt by a mangled finger, injured in a childhood accident. At first Frances, known among the Miami as Ma-Con-A-Quah, or “The Little Bear,” remained stoically indifferent to their presence.

After a couple of days visiting, she relaxed enough to talk about herself with them; but at their urging her to come back to live with them in Pennsylvania, she firmly refused. She said, “No, I cannot. I have always lived with the Indians. They have always used me very kindly. I am used to them. The Great Spirit has allowed me to live with them, and I wish to live and die with them. Your looking glass may be larger than mine, but this is my home. I do not want to live any better, or anywhere else; and I think the Great Spirit has permitted me to live so long because I have always lived with the Indians. I should have died sooner if I had left them. My husband and my boys are buried here, and I cannot leave them. On his dying day, my husband charged me not to leave the Indians. I have a house and large lands, two daughters, a son-in-law, three grandchildren, and everything to make me comfortable. Why should I go and be like a fish out of water?”

She even refused to go visit her relatives in the Wyoming Valley, saying “I am an old tree. I cannot move about. I was a sapling when they took me away. It is all gone past. I am afraid I should die and never come back. I am happy here. I shall die here . . . and they will raise the pole at my grave, with the white flag on it, and the Great Spirit will know where to find me.” And her son-in-law added, “When the whites take a squaw, they make her work like a slave. It was never so with this woman . . . I have always treated her well.” The older daughter, Cut Finger, added “a deer cannot live out of the forest” and the younger, Yellow Leaf, repeated “the fish dies quickly out of water.”

As a later chronicler of the story commented, “they had found the long-lost sister Frances; they found and left her as an Indian. She worked like an Indian, lived like an Indian, ate like an Indian, lay down to sleep like an Indian, thought, felt, and reasoned like an Indian; she had no longings for her original home or the society of her kindred . . . she could only breathe freely in the great, unfenced out-of-doors which God gave to the Red Man.”

Two years later, in 1839, one of Frances’ brothers, with two of her nieces, again made the journey to visit her. The visit went well; and the nieces kept journals of their conversations and observations that have a woman’s perspective. For example, they comment on the cleanness and neatness of Ma-Con-A-Quah’s household, the excellent food served for meals, and the very fine needlework produced by her and her daughters, at least some of it evidently exhibiting skills she had learned as a small Quaker girl in Pennsylvania, then passed on. The grandchildren they met were named Corn Tassel, Blue Corn, and Young Panther. Ma-Con-A-Quah told them of her early life, moving with her Delaware parents from New York to Ohio, marrying a Delaware named Little Turtle.

But when he went west to war with the Americans (in which he was killed), she had refused to follow. Later, she said, while traveling down the Wabash, they came upon the scene of the very recent and bloody Battle of the Fallen Timbers, with bodies still lying on the ground. But one of the battle casualties was still alive, a young Miami chief named She-Pan-Can-Ah.

They rescued him, nursed him back to health, and Frances married him. Ultimately they had four children: two boys who died in childhood, and the two daughters who were still living with her in her old age. She-Pan-Can-Ah, later known as Deaf Man because of a hearing loss, was good to her and left her a wealthy widow by local standards. When her nieces visited her, she invited them and their father, her brother, to come live with her, as she had plenty of land and goods – even as she had been invited two years prior to come live in Pennsylvania.

The next year, 1840, brought a crisis for Ma-Con-A-Quah and her family. The Miami were talked, or coerced, into signing a treaty that required them to vacate all their lands in Indiana and remove to what is now Kansas. Frances and her children appealed to her Slocum relatives to help them in this crisis; and the Slocums submitted a memorial in her name to the United States Congress, asking them to find a way to make an exception for her and her daughters. The family tradition is that the elderly John Quincy Adams took an interest in the plea and supported it.

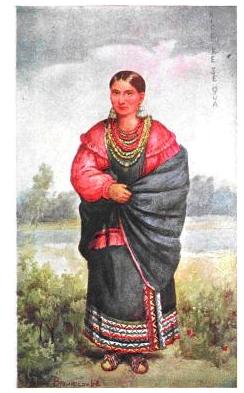

The next year, 1840, brought a crisis for Ma-Con-A-Quah and her family. The Miami were talked, or coerced, into signing a treaty that required them to vacate all their lands in Indiana and remove to what is now Kansas. Frances and her children appealed to her Slocum relatives to help them in this crisis; and the Slocums submitted a memorial in her name to the United States Congress, asking them to find a way to make an exception for her and her daughters. The family tradition is that the elderly John Quincy Adams took an interest in the plea and supported it.Left: Kick-E-Se-Quah

The result was a special grant of a section of land to Ma-Con-A-Quah’s daughters alongside the Mississinewa and exemption from the requirement to move away. Later, when trouble developed with some of the new white settlers in the area stealing cattle and horses from Ma-Con-A-Quah’s land, she asked for, and got, a Slocum nephew, George, with his family, to come live near her, in 1846, as her advocate and protector. She lived a year longer, to the age of 74, and was buried in March 1847 with a Christian service (since her nephew was a minister); but her grave was marked, by her wishes, with a tall pole bearing a white flag in the Indian manner, “so that the Great Spirit should know where she was.” The grave site was on a beautiful knoll near the confluence of the Mississinewa and the Wabash, by the side of her chief and her children, including Cut Finger, who died four days later of “grief and care.”

A Son in Law

And the principles I believe are illustrated in the story of Ma-Con-A-Quah, “The Little Bear,” and her two families – one Quaker, the other Native American – principles evidently lacking in the story of Cynthia Ann Parker? Both stories begin with two apparently inimical cultures and belief systems clashing violently; but in the older story the two families learned eventually to accept one another’s inherent worth and dignity with equity and compassion, followed their conscience, and used a democratic process instead of violence to find a path to peace, liberty and justice. Perhaps there’s a lesson for some of today’s problems in this story.

And I really, really have to hope that my Indiana ancestors weren’t involved in that cattle stealing!

The book is Frances Slocum: The Lost Sister of Wyoming, compiled and written by her Martha Bennett Phelps for her children and grandchildren; second edition, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania; published by the author 1916, copyright 1906 by Martha B. Phelps, Vail-Ballou Company, Binghamton and New York. This is a copy from the Google Library and is prefaced by a statement from Google that the book is in the public domain (i.e., the copyright has expired).

All the portraits are from the book and are copies of original paintings in the possession of the Slocum Family. The painter of the pictures in this article was Jennie Augusta Brownscombe whose early life sounds like the story behind one of her own pictures. Born in a log cabin in rural northeastern Pennsylvania, she was the only child of William Brownscombe, an English-born farmer, and Elvira Kennedy, a direct descendant of a Mayflower passenger, who encouraged her young daughter to write poetry and draw. Brownscombe won her first awards as a high school student, exhibiting her work at the Wayne County Fair. When her father died in 1868, Brownscombe began supporting herself through teaching, creating book and magazine illustrations, and selling the rights to reproduce her watercolor and oil paintings as inexpensive prints, Christmas cards, and calendars. More than 100 of Brownscombe's works were distributed this way, spreading her images into homes throughout the nation.

A prize-winning student at the Cooper Institute School of Design for Women and the National Academy of Design, both in New York City, Brownscombe in 1875 became a founding member of the Art Students League, where she later served on the faculty. Her oil paintings met with immediate success, as both her subjects (sentimental genre pictures and scenes from colonial American history) and her style appealed to prevailing Victorian tastes. Brownscombe studied art in France in 1882, spent the winters of 1886 through 1895 in Rome, and exhibited her pictures there and in London, New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia. She continued working until virtually the end of her long life, completing her final large oil painting at the age of 81 after recovering from a stroke. I found Jennie Brownscombe's signature on at least a couple more of the paintings and am pretty sure she did all of them. Not surprising, since she was well-known for painting American historical subjects for a popular market and has been referred to as "The Norman Rockwell of her era".

notes by John I. Blair

©2009 John I. Blair

Click on author's name for bio.

No comments:

Post a Comment